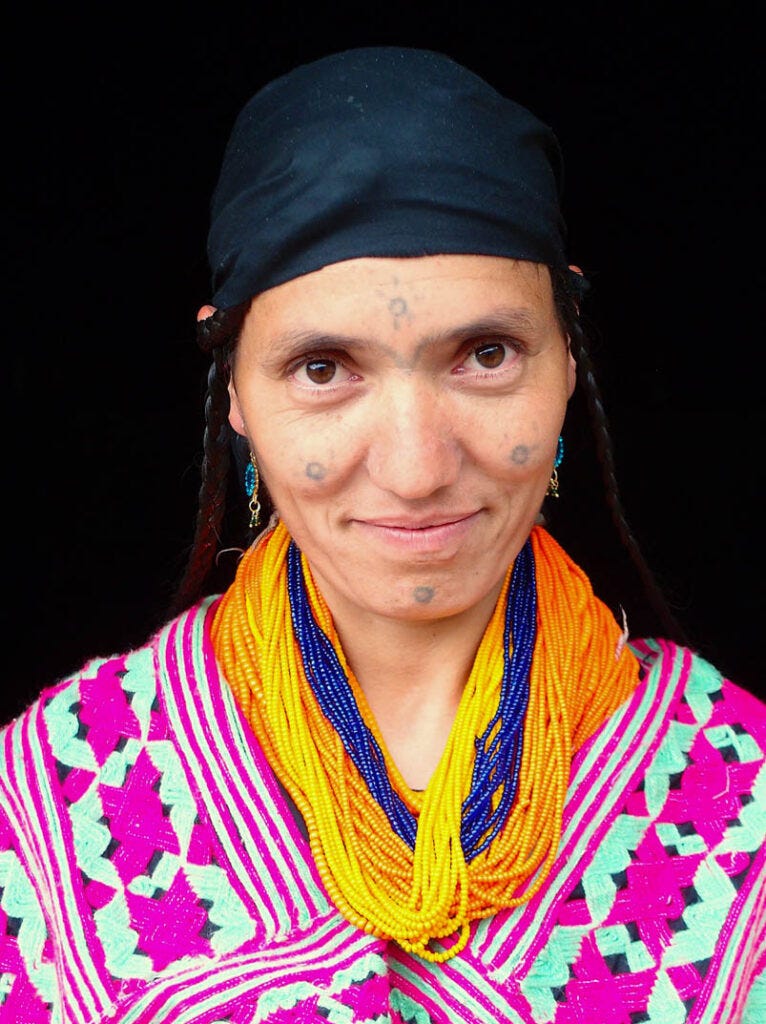

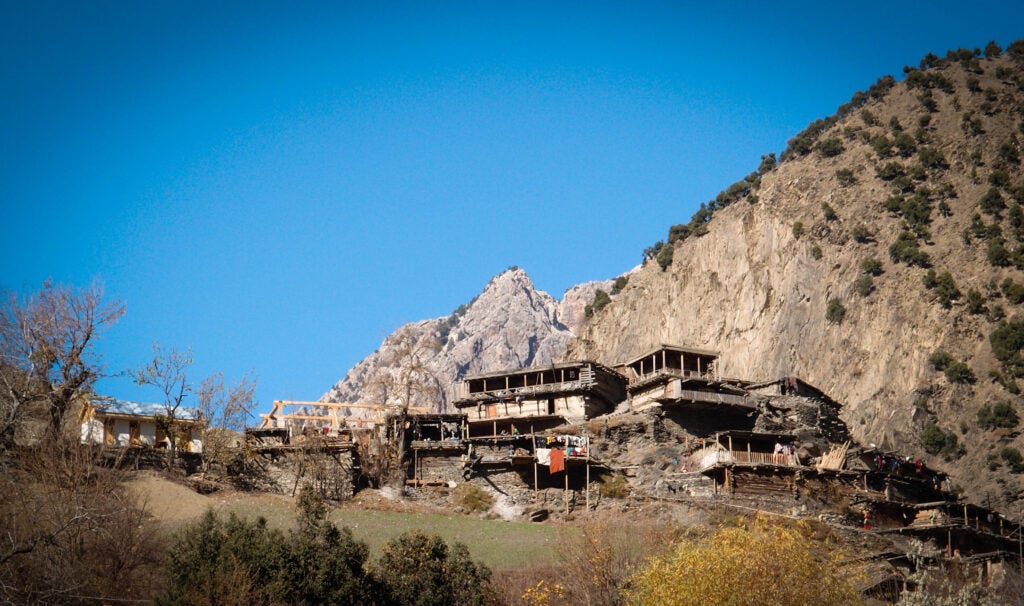

Photos by Ibraar Hussein

“In the time when gods, spirits and human beings lived together in nature with the plants and the animals, everyone communicated, each knew everything about the others”. [1]

Such is the ancient wisdom of the Kalash people of South Asia, their ancestral memory of a Golden Age evoking a belonging to the living world that has been lost from view in the desert of industrial modernity.

The Kalash live up in the Hindu Kush mountains of north-west Pakistan and, until relatively recently, had remained miraculously untouched by the various centralising forces that destroy organic culture everywhere.

Viviane Lièvre and Jean-Yves Loude lived with them, and learned from them, from 1976 to 1990 and paint a fascinating portrait of their society in Le Chamanisme des Kalash du Pakistan.

Rooted societies always enjoy a strong spiritual connection to place and the Kalash honour various lakes and caves as being holy, [2] as part of their “sacred geography”. [3]

The seasons are also part of their enchanted worldview, with the winter solstice festival, chaumos, celebrating “the providential regeneration of society”. [4]

Trees are also regarded as spiritually important. For instance, cedars are believed to be protected by fairies and anyone who chops one down is likely to find themself under an evil spell which can even lead to death. [5]

Before his first outing of the year, a Kalash woodcutter makes an offering of bread and cheese to the nature spirits. [6]

Karl Jettmar writes of the neighbouring Gilgit people: “All trees not planted by men and growing wild are part of the supernatural sphere.

“Cutting them down constitutes interference with the world of spirits.

“If it is considered necessary to fell a tree instead of simply collecting dead wood, a sacrifice (usually of a goat) must be carried out beforehand.

“Even today [1975] this is perfectly obvious for anyone building a house or a bridge”. [7]

The evergreen holm oaks are seen as real natural treasures because they can keep herds of goats fed from the end of October right through to the beginning of June. [8]

And the Kalash have a particular love for junipers, which manage to grow at high altitudes and, as well as feeding goats, also provide essential firewood. [9]

These trees, believed to have been planted by the fairies, feature prominently in the ceremonial life of the Kalash and their neighbours – when burned, their pungent smoke is used to incite shamanic trances. [10]

The juniper is sacred because it enables life in those inhospitable mountains. It is a means by which divine nature cares for her people.

Needless to say, it is to be treated with care and it is only cut down when dead and dry. “If we felled a green juniper, it would be like killing a child”, one Kalash man explains. [11]

This feeling for trees, this knowledge of our deep belonging to the essential Whole, is shared by all humans whose hearts have not been turned to reinforced concrete by the vitaphobic industrial system.

Like all traditional hunting peoples, those of the Hindu Kush have a code of respect for the animals they kill to eat.

“As soon as he kills an animal, the hunter must immediately sing a song, ghoru, in honour of the slain beast, otherwise he will not be able to kill any game in the future”. [12]

Even the feelings of snakes are acknowledged. If one is killed, the person responsible and any other witnesses should place personal objects in a circle around the dead animal, observe a minute’s silence, then throw the body into a river.

In this way, other snakes will not seek vengeance for the killing. [13]

Nature-based folk beliefs like this would once have been held by all our ancestors, before they were declared “heresy” by organised religion and “superstition” by the narrowed-down “scientific” modern mindset.

Lièvre and Loude explain: “Neither Hinduism, nor Buddhism, nor Islam have managed to impose themselves at the expense of the beliefs and practices carried out by the community”. [14]

They say the Kalash dehar, shamans, “have managed to pass on to each generation instructions inspired by the supernatural.

“Adopted by the community, their revelations have been built into customary codes giving the Kalash people a religious specificality, despite external pressures and influences”. [15]

In neighbouring areas which have been converted to Islam, shamans take on a different role – upholding the collective communal ethos from outside the centre of power, they issue warnings or criticisms about the direction that society is taking.

Peter Snoy has given an account of a shaman who, in 1955, sung revelations about a local tax collector.

“He had nothing good to say about him, on the contrary, he claimed that he was oppressing the poor and favouring the rich; misfortune would strike him if he carried on acting that way”. [16]

Lièvre and Loude say that the polytheistic Kalash society is notable for the absence of priests, who are not at all the same thing as shamans.

This is even a point of principle, they explain, with inherited teaching absolutely excluding any cultural monopoly by a priestly class. [17]

And, they add, this ethos permeates Kalash society on every level: “Politically, it does not tolerate central power, like a good number of nomad peoples of the steppes of central Asia or Afghanistan, even though it has been solidly sedentary for a long time now”. [18]

They describe how in the “holistic society” of the Kalash, persistent illness or other problems afflicting one individual or household are regarded as troubling for the well being of the community as a whole and thus the shaman’s intervention in such affairs represents a collective desire to put things right. [19]

This is partly because an illness is itself seen as involving more than the individual’s physical condition and as being “the result of pressure exerted by a part of the community (members alive or dead) with regard to an individual who has disturbed the game of social relationships”. [20]

This is all part of the anarchistic flavour of Kalash society, its idea of an internally-assured balance, free from outside power.

Roberte Hamayon notes: “In fact, we have never seen a shamanic society which, while remaining shamanic, has been centralised, constituted into a state”. [21]

The role of the Kalash shamans is not to lay down religious law but, by entering into a trance, to become a channel between the spirits of nature and human communities.

The ceremonies often feature green branches – universal symbols of our belonging to nature – and the playing of music. The shaman is frequently exhausted by his exertions and collapses at regular intervals. [22]

Hamayon stresses: “Far from being the priest of a god, the shaman is the servant of his community, using for its benefit his capacity for communication with the supernatural”. [23]

Lièvre and Loude add: “The trance is cultural behaviour not only accepted by the community, but valued as irrefutable proof of the manifestation of the sacred in the body of a man, allowing communication between two worlds, visible and invisible, profane and sacred”. [24]

The dehar himself (they are nearly always men) plays an almost passive part in the process. “The message from the supernatural simply comes to him. His role does not involve modifying or interpreting ‘received’ words.

“Moreover, he does not need to dance, or sing, or play an instrument to enter into a trance. His ‘art’ is thus thoroughly spontaneous and needs no instruction. He is a medium, a receiver, a transmitter of information”. [25]

As intermediaries between two worlds, the shamans see the fairies.

Lièvre and Loude say that the Kalash people and their neighbours were originally nomads and when they settled in the Hindu Kush they adopted the nature-spirit beliefs of the original inhabitants.

“The newly-arrived Kalash developed a syncretic attitude reconciling their Indo-Aryan gods with aboriginal fairies”. [26]

However, we Europeans also have a tradition of believing in fairies and other nature spirits, so I am not sure about that particular point.

Indeed, the fairies of the Chitral region are called peris [27] which seems remarkably close to the term esperis, used by Joan of Arc’s prosecutors in 15th century France to describe the fairies, or “spirits”, that she had seen at a sacred fountain. [28]

One Kalash dehar, Djanduli Khan, explains what the fairies look like: “They wear dresses that go down to their knees, leaving the rest of their legs uncovered and their feet bare.

“Their hair is red and hangs loose, coming down to the waist. Their skin is red like that of Westerners”. [29]

In the Gilgit region, the fairies are described as being beautiful, with blond hair and pink skin like European women, and are sometimes specifically said to look like English “ladies”. [30]

There are also less attractive female demons with pendulous breasts which they throw back over their shoulders when they are angry! [31]

Altars are constructed on the mountain slopes in honour of the fairies – Lièvre and Loude describe a ceremony that took place at one of them on May 13, 1987.

“As the sun is setting (around 3pm), men bring branches and foliage from all the trees most important for life and the continuation of society; all symbols of the revitalisation of nature after the winter.

“An extraordinary and most beautiful sight: foliage-men, bent down, camouflaged, advancing under these waving wings of greenery, one behind the other. They place their loads next to the altar dedicated to the fairies”. [32]

If they are kept happy, the fairies will come to people in their dreams and give them advice or warnings. [33]

Like the Kalash community with which they are entwined, the fairies enjoy drinking the local wine (a cultural pleasure which is unusual in that part of the world) [34] and are known to have sex with some local men. [35]

Their human lovers are described as being “mixed with the fairies”, which implies that they behave in an eccentric or bizarre way [36] – a bit like being “away with the fairies”, as we put it in English, I suppose.

So how can we best understand all of this?

If we see the whole of our world, indeed of the cosmos, as a living organism, then this entity must have some way of knowing itself, of feeling itself, of transmitting information within itself.

The shamans who enter into a receptive state of mind are making themselves available to accept that information from the Whole, in a way which was perhaps once possible for all humans.

I would say that the fairies are not so much “supernatural” as a part of nature that we cannot see, measure or fully grasp.

Lièvre and Loude write of “that permanent human desire to understand the language of the spirits and the plants, as in primordial times”. [37]

The fairies, and the shamans, are speaking that language and relaying messages from the Whole – they are part of the invisible nervous system by which it knows, feels and regulates its being.

Their magic is the magic of the living universe to which we all still very much belong, despite the spiritual numbness, blindness and denial of this wretched modern age.

All the photos are by my friend Ibraar Hussein, who recommended the book to me and whose wonderful photography can also be found here. Many thanks Ibraar!

[1] Viviane Lièvre and Jean-Yves Loude, with the collaboration of Hervé Nègre, Le Chamanisme des Kalash du Pakistan: Des montagnards polythéistes face à l’islam (Lyons: Presses universitaires de Lyon, 2018), p. 147. All following page references are to this work, unless otherwise stated. There is an English version of the book, but obviously my own translations here will not correspond exactly to that text.

[2] p. 46.

[3] p. 140.

[4] p. 182.

[5] p. 90.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Karl Jettmar, Die Religionen des Hindukusch, vol 1 (Stuttgart: 1975), cit. p. 90.

[8] p. 100.

[9] p. 54.

[10] Ibid.

[11] p. 54.

[12] Shahzada Hussam-al-Mulk, ‘Chitral Folklore’, Karl Jettmar and Lennart Edelberg (dir), Cultures of the Hindukush: Selected Papers from the Hindukush Cultural Conference, Moesgard 1970 (Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1974), pp. 109-10, cit. p. 77.

[13] p. 317.

[14] p. 529.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Peter Snoy, Bagrot: Eine Dardische Talschaft im Karakorum (Graz: Akademische Druck-u-Verlagsanstalt, 1975), p. 197, cit. p. 306.

[170] p 160.

[18] p. 146.

[19] p. 313.

[20] p. 372.

[21] Roberte Hamayon, ‘Des chamanes au chamanisme’, L’Ethnographie, No 87-88, 1982, pp. 13-48, cit. p. 304.

[22] p. 26.

[23] Hamayon, p. 32, cit. p. 227.

[24] p. 434.

[25] p. 440.

[26] p. 161.

[27] p. 48.

[28] Paul Cudenec, The Green One, 2017, p. 160.

https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/the-green-one-1.pdf

[29] p. 48.

[30] Jettmar, p. 220, cit. p. 48.

[31] p. 48.

[32] pp. 57-58.

[33] p. 76.

[34] p. 120.

[35] p. 76.

[36] p. 78.

[37] p. 56.

How fascinating!

Also, that the sun was setting around 3pm on May 13th — a mere 4 weeks shy of summer solstice — at a latitude of mid-30's North, really speaks to the depths of the valleys and the heights of the mountains. A quick glance at Wiki suggests there are eleven 20,000 ft plus peaks in the Hindu Kush.

Truly Beautiful