The global industrial-financial complex has been doing its best for decades now to ensure there is no real ideological opposition to its life-hating agenda.

In part, it achieves this through relentless propaganda assuring us that its brutal assault on humankind and nature amounts to “progress” or “growth” or “innovation” or positive “change”.

It has also taken care to ensure that its apparent political enemies stop short at opposition to the form its rule happens to take at any one time and in any one place, and never challenge its essence, which is the relentless trail of destruction it calls “development”.

Thus Marxism, at the very core of its outlook, insists on the so-called “need” for this process, as I set out in ‘The false red flag’. [1]

And its supposed diametric “opposites”, Italian Fascism and German National Socialism, were also used to push through an acceleration of the “modernisation” so dear to the criminocracy.

The system also constantly attacks, ridicules and shames anyone who dares to question the wisdom of its greed-fuelled “progress”.

We are labelled “reactionaries”, “cranks”, or “tree-huggers”, who want to “drag us back to the stone age”.

Ironically, we are also sometimes smeared with alleged ideological association with one of the fake and pro-industrialist opposition movements groomed by the global mafia, namely Nazism.

I wrote an essay in 2018 about how the system presents a misleading image of continuity between the “back to nature” movement in Germany at the start of the 20th century and Hitler’s regime. [2]

The truth is that the language and imagery of this deeply anti-industrial movement were co-opted by the Nazis to gain support for their ultra-industrial programme – in the same way that the mainstream “green” movement today has been captured and used to advance the “sustainable” Fourth Industrial Revolution.

For in-depth analysis of this phenomenon, I’d refer you back to the earlier piece, but I recently came across some fascinating confirmation of how this historical falsification is engineered.

It revolves around the career and philosophy of the German thinker Ludwig Klages (1872-1956), whom I will examine in this series of three essays.

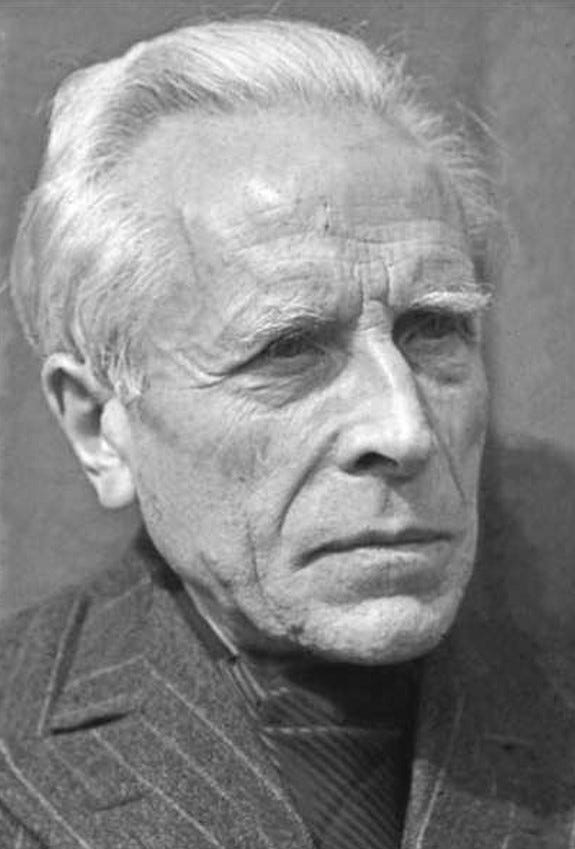

In the first decades of the twentieth century, Klages (pictured) was considered to be an important intellectual figure.

As Paul Bishop sets out in his 2018 book, Ludwig Klages and the Philosophy of Life, to mark his 60th birthday in 1932, the year before Adolf Hitler came to power, he was presented with the Goethe Medal for Art and Science by the German president, Paul von Hindenburg, and numerous newspapers in the country “published articles congratulating him and presenting overviews of his philosophy”. [3]

His many admirers included the novelist Hermann Hesse, who wrote of one of Klages’s books that it had “such psychological depth and rich fruitful atmosphere” that in some parts “something almost inexpressible has found the right words”. [4]

The philosopher Karl Jaspers attended Klages’s “psychodiagnostic seminar” in Munich [5] and offered the independent scholar an academic position in Heidelberg. [6]

He was appreciated by philosopher Ernst Cassirer and philologist Walter F. Otto, [7] while the Austrian novelist Robert Musil, whom he met in Vienna, based one of the key characters in his great novel The Man Without Qualities on Klages. [8]

But subsequently, as Bishop remarks, “something strange” has happened: “Even though his work was lauded by numerous contemporary thinkers as a landmark in twentieth-century thought; even though he earned the highest of praise… Klages has completely disappeared from the cultural scene in general and the philosophical scene in particular”. [9]

The reason for this is easy to discover: “Klages – if he is mentioned at all – is usually only ever named in order to be swiftly dismissed for his alleged right-wing (and, more specifically, anti-Semitic) views”. [10]

Nitzan Lebovic, in his 2013 book about Klages, describes how his Lebensphilosophie, his life philosophy, has been treated by certain analysts, such as George Mosse, as the intellectual basis of the supposed “irrationalism” of the fascist “third force”. [11]

This take on his work was already being voiced in 1935 by Thomas Mann, who branded Klages a prefascist, “an irrationalist” and even a “criminal philosopher”. [12]

Remarks Lebovic: “The earlier positive reception of Lebensphilosophie among radicals on the left was ignored and suppressed”. [13]

Extreme hostility towards Klages, in some quarters, has lived on into the 21st century.

In 2006 Edward Skidelsky, in the UK “left-of-centre” magazine New Statesman, branded him an “anti-Semitic crank” [14] and in 2008, in an article in the US conservative magazine, National Review, Jonah Goldberg referred to Klages as a “proto-Nazi philosopher (and rabid anti-semite)”. [15]

Bishop, for one, is having none of it, declaring with great clarity: “I believe that Klages is not a fundamentally anti-Semitic thinker, not a right-wing philosopher, and not a Nazi”. [16]

But on what basis can we confirm this conclusion, in the face of all the critical venom?

Lebovic, himself Jewish, describes his book as “a plea for openness” [17] and points us to Klages’s “close relationship with Jews since his youth”. [18]

He writes: “Interestingly enough, on the occasions when Klages expressed intellectual admiration, it was more often for Jews than for non-Jewish Germans.

“Three Jews – Theodor Lessing, a childhood friend, and Karl Wolfskehl and Richard Perls, two Jewish disciples of Stefan George – made the most radical impression on him during the first three decades of his life, and he admired Melchior Palagyi, a Hungarian Jewish philosopher and physicist, in the second half of his life”. [19]

Klages regarded Palagyi as “his scientific soul mate”, adds Lebovic. [20]

Jewish appreciators of Klages’s work included Karl Lowith, [21] Emil Utitz, [22] and Friedrich Salomon (Shlomo) Rothschild [23] – Klages even gave a paper at the Viennese Psychoanalytic Society at the invitation of Sigmund Freud. [24]

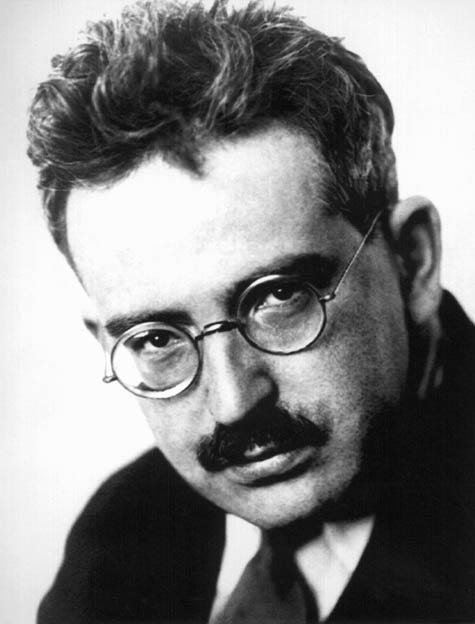

The most important connection, though, was perhaps with the “left-wing” German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin (pictured).

Benjamin first read about Klages’s work in 1914, when he was 22 years old, and travelled to Munich in order to invite the author to lecture to his fellow Free German Students, the liberal branch of the back-to-the-land Wandervogel movement.

The younger man found the elder one “forthcoming and polite”, [25] and continued to correspond with him.

In 1930 Benjamin recommended to his close friend, Gershom Scholem — a Kabbalah scholar living in Jerusalem — that he read a book by Klages that was “without doubt a great philosophical work”. [26]

And then, between 1935 and 1937 Benjamin tried (and failed) to convince Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer of the Frankfurt School to finance a book that would sketch a theory of the collective unconscious and fantasy, based on the writings of Klages and Carl Jung. [27]

Muses Lebovic: “One wonders what could have united an apolitical, conservative, romantic autodidact with an urban sophisticate highly alert to politics and culture”. [28]

He says there was a revolutionary appeal for Benjamin in these theories that opened a window on the “primal past”. [29]

“A primary source for Benjamin was Klages’s Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele (Spirit as the adversary of the soul), published in three parts between 1929 and 1932″. [30]

He adds: “There is little doubt that Benjamin first encountered the concepts of Rausch [ecstasy] and nonlinear dream images, both vital to his phantasmagoria, in Von Traumbewusstsein” – one of Klages’s other works. [31]

For Klages, one of the main barriers preventing us from accessing the ecstasy of our primal past was the Judeo-Christian tradition.

His criticism of Judaism and “Yahwehism” [32] was therefore part of a broad rejection of patriarchal religion, our separation from the natural world, the domination of narrow-minded, materialistic, “rational” and “scientific” thinking – he was turning his back on the modern mindset.

Lebovic explains: “From Klages’s perspective, if Judeo-Christianity created the linearity of world history, as expressed in idealism and the modern state, he strived to reach the language of pure signs.

“Biblical linearity he considered a progressive abstraction and therefore corrupting, while a pure language was stable and imagistic, and therefore true.

“For Klages, there was a line connecting the traces of a biblical theology with the modern scientific systems and the Enlightenment”. [33]

His preference, following Johann Bachofen, was for the Magna Mater (Great Mother) over Jahwes Gesetz (Jehovah’s Law). [34]

Klages and his circle aimed to pay homage to pagan myths older than Judaism and Christianity and to spread “a sort of religiosity connecting the individual to the universe by cosmogonic Eros”, writes Gilbert Merlio. [35] This was meant to counter the “disenchantment of the world” famously cited by Max Weber, he adds. [36]

Klages’s objection to modern civilisation was in the tradition of Kulturkritik, rejecting utilitarianism, egotism, the worship of “success”, the prioritising of having over being. [37]

Alongside this supposed “cultural anti-Semitism”, [38] there is Klages’s strong opposition to Zionism [39] and his awareness of the reality of contemporary Jewish power and influence, notably via finance and the media.

For instance, he writes about the way that so-called public opinion “is made by the daily newspapers, obviously in the service of the dominant world of finance”. [40]

He cites all the propaganda which whipped up public support in the USA for the country’s participation in the First World War, a bloodbath that we now know was deliberately organised and prolonged by the Rothschildian empire. [41]

Klages rightly points out: “That sort of thing was written in the papers because a handful of high dignitaries of mammon expected extremely lucrative business for themselves from America’s participation in the war”. [42]

His philosophy, as we will see in the second of these three essays, is incredibly erudite and complex and he resented the hostile reduction and misrepresentation of his work in what he called “the Jewish press”. [43]

As Bishop notes, there is a vast gulf between Klages’s “cultural critique of Judeo-Christianity” and “racial anti-semitic policies, leading to the Holocaust”. [44]

One could say that Klages is challenging what contemporary anti-Zionist academic David Miller terms “Jewish privilege” – culturally and socially. [45]

Far from labelling Jews inferior and inciting down-punching attacks on Jewish individuals, as Nazi propaganda did, he is punching upwards against a system which he feels is thwarting humankind’s true potential.

He declares: “I have never endorsed the claim that the Nazi big-wigs belonged to a superior race.

“However, I must also add that I have consistently refused to accept the claim of another such race as the chosen people”. [46]

While accusations of “anti-semitism” against Klages are therefore spurious, suggestions that he supported the Hitler regime are simply ridiculous.

Writes Bishop: “One of the most commonly heard charges made against Klages is that he sympathised with the National Socialists. As we shall see, however, nothing could be further from the truth”. [47]

His opposition to the militarism and industrialism that characterised Nazism was already in evidence when in 1915 he fled Germany for Switzerland, with the aim of “inhabiting a place that suited his romantic ideals, a land still untouched by the pollution of urbanization and mechanization”, as Lebovic puts it. [48]

While some of Klages’s ideas were appreciated by some Nazi supporters, and some followers of Klages ended up participating in their regime, there were serious differences between Klages’s philosophy and National Socialist politics, as Bishop sets out in a table in his book. [49]

For one thing, while the Nazis were interested purely in German paganism, Klages was interested in all forms of paganism.

The Nazis also emphasized the very instrumental reason which Klages critiqued, they were enthusiastic about the modern technology that Klages opposed and they abused the natural world for which Klages urged care and nurturing!

These differences were apparent in the very first year of the Third Reich, 1933, when the Nazi philosopher Alfred Bäumler (pictured) wrote a report rejecting “the assumption that Klages has, in any way, prepared the way for National Socialism”. [50]

Bishop recounts: “The political leadership of the National Socialist dictatorship soon realised there was a huge discrepancy between its own political goals and the critical stance towards modernity proposed by Klages.

“In 1934, Hans Eggert Schröder became the director of the Working-Group for Biocentric Research (Arbeitskreis für biozentrische Forschung), a group of scholars and researchers seeking to spread Klagesian ideas.

“On his own account, in 1936 Schröder received a letter from the State Secret Police, ordering him to close down the Working-Group; and in 1938, he was warned by the Reich’s Department for the Support of German Writing, an office under the control of one of the chief Nazi ideologues Alfred Rosenberg (1892/3-1946), to desist from publishing articles about Klages”. [51]

Rosenberg even attacked Klages in a public address in April of that year, very clearly distancing the Nazi philosophy from Klages’s. [52]

A veritable campaign against Klages’s thought was launched – Rosenberg’s speech was widely reported in the Nazi press and reprinted in full in the cultural organ of the NSDAP, the National Socialist Monthly (Nationalsozialistische Monatshefte), before being published separately as a pamphlet-length book.

Rosenberg (pictured) even organised a training week for his staff in the summer of 1938. Reports Bishop: “The purpose of this training was to help them to combat different forms of what National Socialism described as ‘sectarian’ thought.

“Under this rubric fell various intellectual tendencies deemed incompatible with National Socialist ideology, including Oswald Spengler, the members of the circle around Stefan George, and Ludwig Klages and his followers.

“In a ‘Parliamentary Expert’s Report of the Rosenberg Department’, we find the following declaration: ‘The official appointed by the Führer to be responsible for the entire intellectual and ideological education of the NSDAP has, through its timely intervention, prevented universalism from contaminating National Socialism; he is equally determined to avoid any kind of mingling of the “biocentric” world-view with National Socialism'”. [53]

So given that Klages was not a Nazi sympathiser, and that his ideas were even regarded as a threat by Hitler’s regime, how might we describe his political position?

The question is a complex one, because the whole point of his philosophy is to escape the narrow confines of conventional thinking and labelling, to access a different dimension of consciousness.

Lebovic says that his Lebensphilosophie “rose as an aesthetic avant-garde, favoring a pure art of living or living style above any form of politics”. [54]

“It was especially those intellectuals standing between right and left that were most interested in Lebensphilosophie for its radical philosophical potential”. [55]

“Lebensphilosophie took over the popular communal discourse because it offered the only authority one could rely on: the horizontal, non-hierarchical experience of life”. [56]

“Klages never affiliated himself with any political party, though he was certainly sympathetic to some radical groups that worked against the system as a whole.

“One finds an odd mixture of anarchism and reactionary order in his rare political comments of the early 1920s”. [57]

Indeed Lebovic cites author Martin Green in seeing a “striking likeness” between Klages and the anarchist Otto Gross, not least in their shared interest in Bachofen’s theories about ancient matriarchal society. [58]

And he also refers to similarities with the approach of the English eco-anarchist John Moore, who died in 2002, particularly his 1988 monograph Anarchy and Ecstasy: Visions of Halycon Days which presents a “sacred wilderness” and “a politics that doesn’t look like politics”. [59]

This is a philosophical-political realm where the “usual” categories make no sense.

Klages certainly, as Bishop says, “developed an urgent critique of the modern world, and pioneered the cause of environmentalism”. [60]

Merlio describes his Mensch und Erde, which we will consider in more detail in the last of these three essays, as “the first modern ecological manifesto”. [61]

But, following the Romantic tradition, its critique of capitalism is not of the “left-wing” or Marxist kind, but is essentially moral and drawn from a deep-rooted aversion to “mammonism”. [62]

Klages’s writing, says Merlio, illustrates the fact that environmentalism originally arose from the political “right”.

At the start of the 20th century, this was split into technocratic and environmentalist camps, with Klages belonging to the latter.

But this was a “right” unlike any we have seen since – a “right” which challenged the existing industrial order and thus presented revolutionary potential.

While the “left-wing” version of environmentalism that eventually prevailed might be imagined – if we accept the reputation of these labels – to be more revolutionary, this is not the case, as Merlio points out.

“It sees itself as generally progressivist and in any case is no longer distinguished by an absolute rejection of the exploitation of nature by science and Technik, but dreams instead of sustainable development, of clean and green growth”. [63]

In this context, Klages’s supposedly “conservative” environmentalism represents the genuinely radical version.

Concludes Merlio: “If we wanted to attach him to a current of contemporary environmentalism, we would have to think of what is termed ‘deep ecology'”. [64]

This, of course, is really why Klages has been sidelined and smeared by the system.

It is not because his life philosophy is actually “anti-semitic” or “pro-Nazi”, but because, as we will see in the following essays, it offers a powerful and profound beyond-left-and-right challenge to the global financial-industrial Leviathan.

See also:

Life philosophy: soul, rhythm, magic and love

Life philosophy: against the destructive will of Mammon

[1] Paul Cudenec, ‘The False Red Flag’, Against the Dark Enslaving Empire! A condemnation of the global criminocratic conspiracy (Winter Oak, 2024), pp. 67-111.

https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/against-the-dark-enslaving-empire-online.pdf

[2] Paul Cudenec, ‘Organic radicalism: bringing down the fascist machine’, Fascism rebranded: exposing the Great Reset (Winter Oak, 2021), pp. 1-71. https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/fascism-rebranded23web.pdf

[3] Paul Bishop, Ludwig Klages and the Philosophy of Life: A Vitalist Toolkit (Abingdon/New York: Routledge, 2018), p. 28.

[4] Hermann Hesse, ‘Über die heutigen deutsche Literatur’ (1924), Bishop, p. xi.

[5] Nitzan Lebovic, The Philosophy of Life and Death: Ludwig Klages and the Rise of a Nazi Biopolitics (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), p. 80.

https://www.thetedkarchive.com/library/nitzan-lebovic-the-philosophy-of-life-and-death.pdf

[6] Lebovic, p. 161.

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludwig_Klages

[8] Lebovic, p. 132.

[9] Bishop, p. xvii.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Lebovic, p. 15.

[12] Lebovic, p. 14.

[13] Ibid.

[14] E. Skidelsy, ‘The ideas Corner: A Less than Perfect World’, New Statesman, 31 July 2006, cit. Bishop, p. xvii.

[15] J. Goldberg, ‘A Half Century’s Slander: It Isn’t Conservatives Who Must Answer for Fascism’, National Review, 28 January 2008, cit. Bishop, p. xvii.

[16] Bishop, p. xix.

[17] Lebovic, p. 9.

[18] Lebovic, p. 64.

[19] Lebovic, p. 33.

[20] Lebovic, p. 197 FN.

[21] Lebovic, p. 168.

[22] Lebovic, p. 175.

[23] Lebovic, p. 176.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_S._Rothschild

[24] Bishop, p. 8.

[25] Walter Benjamin to Ernst Cohn, June 23, 1914, in The Correspondence of Walter Benjamin, 1910-1940, trans. Manfred R. Jacobson and Evelyn M. Jacobson (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), p. 69, Lebovic p. 85.

[26] Walter Benjamin to Gershom Scholem, March 15, 1930, in Gershom Scholem and Theodor W. Adorno, eds., The Correspondence of Walter Benjamin, trans. Manfred R. and Evelyn M. Jacobson (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1994), pp. 366-367, Lebovic, p. 19.

[27] Lebovic, p. 109.

[28] Lebovic, p. 158.

[29] Lebovic, p. 157.

[30] Lebovic, p. 196.

[31] Lebovic, pp. 157-58.

[32] Lebovic, p. 51.

[33] Lebovic, p. 79.

[34] Lebovic, pp. 199-200.

[35] Gilbert Merlio, ‘Préface’, Ludwig Klages, L’Homme et la terre (Mensch und Erde), trad. Christophe Lucchese (RN Editions, 2016), p. 9. Quotations from this book are my own translations from French.

[36] Merlio, p. 15.

[37] Merlio, p. 18.

[38] Lebovic, p. 42.

[39] Lebovic, p. 52.

[40] Ludwig Klages, Die Grundlagen der Charakterkunde, Sämtliche Werke 4, ed. Ernst Frauchiger, Gerhard Funke, Karl J. Groffmann, Robert Heiss and Hans Eggert Schröder, 9 vols (Bonn: Bouvier, 1964-1992), p. 408, Bishop, p. 96.

[41] See Paul Cudenec, ‘A crime against humanity: the Great Reset of 1914-18’, The Great Racket: the ongoing development of the criminal global system (Winter Oak, 2023), pp. 136-202. https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/the-great-racket.pdf

[42] Klages, Die Grundlagen der Charakterkunde, Sämtliche Werke 4, p. 408, Bishop, p. 96.

[43] Lebovic, p. 202 FN.

[44] Bishop, p. 35.

[45]https://x.com/Tracking_Power/status/1824157179533824306

[46]

Hans Eggert Schröder, Ludwig Klages, Die Geschichte Seines Lebens, published 1992), § 1350.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludwig_Klages

[47] Bishop, p. 32.

[48] Lebovic, p. 90.

[49] Bishop, p. 35.

[50] Lebovic, p. 118.

[51] Bishop, p. 33.

[52] Bishop, p. 33.

[53] Völkische Beobachter, No 158, 7 June 1938, in Hans Eggert Schröder, Ludwig Klages 1872-1956: Centenar-Ausstellung 1972 (Bonn: Bouvier Verlag Herbert Grundmann, 1981), p. 115, Bishop, pp. 34-35.

[54] Lebovic, p. 92.

[55] Lebovic, p. 195.

[56] Lebovic, p. 95.

[57] Lebovic, p. 112.

[58] Martin Green, The Von Richthofen Sisters, The Triumphant and the Tragic Modes of Love (New York: Basic Books, 1974), pp. 77, 81, Lebovic, p. 140.

[59] Lebovic, p. 153 FN.

[60] Bishop, p. 9.

[61] Merlio, p. 7.

[62] Merlio, p. 18.

[63] Merlio, p. 22.

[64] Merlio, p. 22.

“The truth is that the language and imagery of this deeply anti-industrial movement were co-opted by the Nazis to gain support for their ultra-industrial programme – in the same way that the mainstream “green” movement today has been captured and used to advance the “sustainable” Fourth Industrial Revolution.” — Excellent analogy!

The reason “...Klages has completely disappeared from the cultural scene in general and the philosophical scene in particular” (Bishop), is what it always is: it's the price paid for being over the target.

“This, of course, is really why Klages has been sidelined and smeared by the system.” — That and, I would suggest, “Klages’s strong opposition to Zionism” you mentioned earlier. Openly expressing an unwillingness to kiss the Zionist ring has its consequences.

Mr. Cudenec,

Reading one of your pieces never fails to open a door to a larger world I never knew existed. It's exhilarating! Thank you.