[Plus audio version]

As the bulldozers of power and control progressively destroyed organic folk customs and beliefs across the world, some areas held out for longer.

One such place was the south of Italy, which in the 16th century was described by Jesuits as an “Italian India” [1] – this was not meant as a compliment!

Its most famed tradition is taranta, which is much more than the similar dance today represented on stage.

From his investigations in 1959, anthropologist, historian and philosopher Ernesto de Martino (1908-1965) found that tarantismo in the province of Salento then still influenced directly “the ideology and behaviour of several thousand people”. [2]

It is essentially a form of shamanic ritual, not so different from the ceremonies of the Kalash people that I recently described, [3] except that in this case the participants are mostly women. [4]

The idea is that the music and dance are a cure for having been bitten by local poisonous spiders (not those we call “tarantulas” in English) or by scorpions.

There is no quick cure – it generally goes on for two, three or four days, although de Martino records one case where 18 days of music and dance were needed to expel the toxin! [5]

Neither is it usually a one-off: the “first bite” generally occurs around the beginning of puberty [6] and then the person can be “re-bitten” and re-cured on a regular basis for as long as 30 years. [7]

De Martino judges it unlikely that these people are really bitten by poisonous spiders on every such occasion, even though it is certainly possible, particularly for those who work in the fields.

But the idea of the cure is an old one, with records showing that Norman soldiers in Palermo, Sicily, were treated for spider bites with music and dance nearly a thousand years ago, in 1043. [8]

And the spider is certainly the focus of the folk custom.

The dancer acts out, at one and the same time, the effects of being bitten by a spider and of becoming a spider.

De Martino describes watching a woman dressed in white, a scarf tied around her waist, her black hair in wild disarray over a face wearing an ostentatiously hard and fixed expression, her eyes sometimes open, sometimes shut. [9]

To the sound of guitar, violin, accordion and tambourine, her movements “visibly mimed a being incapable of standing upright and which moved forward almost glued to the floor, in other words a spider.

“The dancer was thus living out her identification with the spider and, a slave to the animal, danced with it, herself became the dancing animal. At this moment there was total identification with the spider”. [10]

As the dance evolved, and quickened in pace, her feet observed a rhythm of 50 beats every ten seconds and, after a particularly frantic spinning phase, she collapsed – just like the Kalash shamans.

“The band stopped playing, the dancer was brought a cushion for her head, assistants mopped abundant sweat from the musicians, then after a break of about ten minutes, the band started up again and the cycle repeated, with always the same phases”. [11]

It used to be widespread, says de Martino, for dancers to be suspended from a tree, or a ceiling, on a rope swing, mimicking a spider hanging from its threads. [12]

The dancer’s relationship with the spiders can be intense, even outside the ceremonies.

De Martino describes one case: “Each year Matilde was again bitten and re-bitten by the spiders: she saw them, felt their sting, called them by their names (Rosina, Marie-Antonietta…) and answered their call.

“These spiders gave her orders, forbidding her, for instance, to eat certain types of food, making her dress in a certain way, telling her to stay away from certain people: and she had to obey these little tyrants, otherwise they would get their own back by giving her the feeling of being ‘injured'”. [13]

The spiders here seem to be playing the same role as the Lakash fairies in representing the intermediary nerves between the individual’s unconscious and the being of the organic Whole, thus providing advice and guidance from beyond the limited perspective of the conscious ego.

Real spiders are also widely reported to respond to the music and take part in the dance.

De Martino explains that the father of one dancer, Carnela, had told him that she danced in the summer (as is usually the case) “because in this season the spider’s web is dry and tight and the spider can easily dance and run on its threads, communicating its movement to the girl.

“In winter, on the other hand, the web becomes damp and soft and cannot bear the weight of any dancing by the spider, which stays motionless at the centre of its web, leaving the girl in peace”. [14]

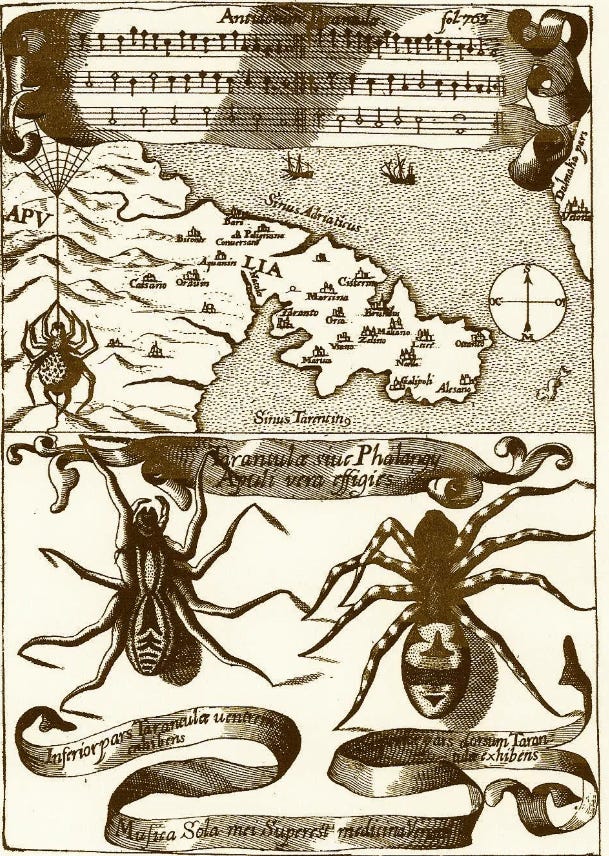

A book published in Rome in 1641 by the scholar Athanasius Kircher describes an experiment carried out by a duchess in the presence of her courtiers and a number of priests.

“To start with, at the sound of the guitar, the spider showed no sign of movement, but, afterwards, when the musicians played a melody appropriate to her mood, the creature not only seemed to carry out a dance by hopping around on its legs and moving its body, but danced for real by respecting the beat; if the musician stopped playing, the creature also stopped its dance”. [15]

De Martino writes that, according to tradition, “spiders seem sensitive to music and dance and, depending on their size and their colour, they prefer one melody or the other; moreover, through their bite and their venom, they communicate their preference to those bitten so that to spark the dance that will act as the cure, the musicians must, by trial and error, determine the melody suited to the case, the one that binds the spider and the bitten”. [16]

Scorpions can get in on the act, as well, as was explained to de Martino.

“The whole family was in agreement in confirming that while Carnela was dancing, the scorpions arrived from the end of the neighbouring garden and came up to the house, as if fascinated by the music; on the last occasion a scorpion had even come into the bedroom and had started dancing on the floor to the same rhythm as Carnela”. [17]

Referring to Plato’s thought about the power of music and dance, de Martino makes a comparison between the way young babies are calmed by singing and rocking and the fact that we are all rocked by the cosmic rhythms of mother nature. [18]

This reminds me of the German philosopher Ludwig Klages and his insistence that the rhythms of reproduction, of life and death, of the stars and planets, of the ocean’s waves and of human hearts are the pulse of one great living.

He said that we can access a different dimension of existence by allowing ourselves to follow that life rhythm – for example, when, in dancing, we lose ourselves and become part of the pulsating universe.

“The more the dancer is granted the grace of becoming completely absorbed in the dance, the more it is not about movements, not about a change of locations and a measuring of line segments, but about the will-less, indeed almost impulse-less, resonance in the element of a wave creating motion, which henceforth experiences and, while it is experiencing, at the same time is ‘worked and woven’.

“In the rhythmically perfect dance something reaches its consummation as a primordial unique experience which, in the meantime, is experienced only at the sight of falling leaves, passing clouds or the surge of ocean waves: the sense of being carried away by the stream of things in action”. [19]

It is here that we might touch ecstasy or Rausch, which Klages defines as “to be outside oneself” and “outside the ego”. [20]

This is, of course, very much the case with tarantismo, shamanism in the Hindu Kush and countless other such traditions across the world.

By passing beyond the restraints of our individual identity we rediscover our always-present belonging to the Whole.

Another intriguing element is that of colour. Spiders are said to have their own favourite colours, which point to the appropriate cure.

Kircher wrote in the 17th century: “The different spiders create in those bitten a passion for different colours… so that those who were bitten by a red spider have a liking for red; those who were bitten by a green spider have a liking for green, and so on.

“That the spiders take pleasure from a certain colour is proven by the fact that if you place them on various coloured surfaces, they choose that of a similar colour to their own”. [21]

Not only is the scene of the “exorcism” – as de Martino calls it – decorated in the right colour, such as red or green, but the band also plays a tune known as the red or green one. [22]

He explains that because the spider dances to a rhythm and music which suit it, “its bite participates in the melody, in the dance, in the colours – it communicates, to the person who endured it, the corresponding preferences and injects into their veins a poison whose harmfulness lasts as long as the spider is alive and whose effects come to an end when the bitten person, thanks to the agonistic identification of the dance, makes the poisoning creature ‘die'”. [23]

Colours, like music and rhythm, form part of the cosmic pattern that underlies the human mind and experience.

They are part of the web of life and the meaning of things – a meaning which has been rendered largely invisible by the empty modern “scientific” mindset.

I stressed in a recent article that folk customs are not fixed and rigid re-enactments but fluid and ever-evolving expressions of our belonging. [24]

And trying to trace the exact origins of a tradition like tarantismo is not easy, as de Martino discovered.

He notes similarities with the Dionysian cult, [25] notably the feminine involvement, thus providing a hypothetical link not just to ancient Greece, but on to India, as explored in the work of Alain Daniélou, which I recently discussed.

He too places tarantismo within the Shaivite and Dionysian tradition and sees similarities with the spinning dances of the Sufis in the Islamic world. [26]

De Martino says that Dionysus was the most important god in the Taranto province where the dancing has its roots.

“During the Dionysian festivities, the whole town descended into intoxication and the arrival of the Roman fleet in 282 surprised the citizens in their celebration of this occasion”. [27]

But de Martino also suggests an “Afro-Mediterranean” origin to the custom, enhanced perhaps by the rapid expansion of Islam in the 8th century. [28]

He cites research by French historian Henri Jeanmaire (1884-1960) regarding the origins of the broader Dionysian tradition.

“In the course of his analysis of the mania and menadism among the Greeks, Jeanmaire has drawn attention to a range of structurally similar African cults (zar, bori etc) characterised by demonic possession and by a choreographic-musical treatment of this possession.

“The areas in which these cults could be found would appear to include (at least according to the relevant data in our possession), the Islamic countries of North Africa (Egypt, Libya, Tunisia), the Arab peninsula, Ethiopia and an important part of the lands of Sudan, as far as the basin of the lower Niger.

“To this sphere as indicated by Jeanmaire, we must add its historical offshoot, the Afro-American world (Afro-Brazilian, Afro-Cuban, Afro-Haitian) where cults of an analogous structure developed, with particular modalities and under various names (macumba, candomblé, santería, voodoo“. [29]

He adds: “The comparison between tarantismo and the voodoo cult is particularly instructive”. [30]

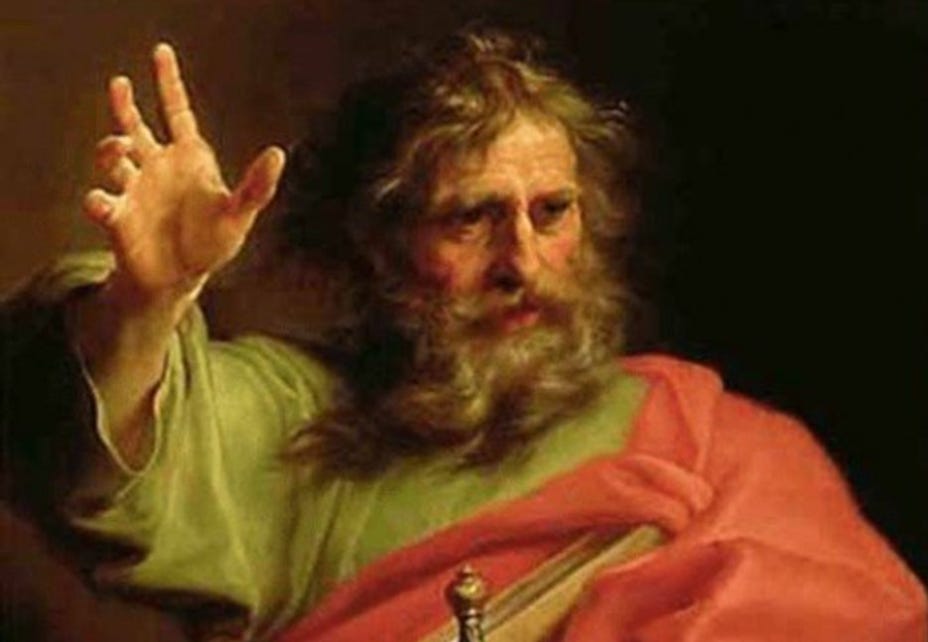

Something I find very intriguing is the way in which, like the tradition of Sophia, or Divine Wisdom, [31] tarantismo combines pagan and Christian elements.

It is particularly tied in with my namesake, Saint Paul, who is regarded as intimately linked with the spiders.

De Martino questioned a 70-year-old woman, Filomena, who was bitten by a spider, as to why she had not killed it, when she had had two occasions to do so.

“She replied that the spider was ‘a creature of Saint Paul’ and that killing it would offend the saint. Her husband, for his part, confirmed that the spider had been ‘sent by the saint'”. [32]

Indeed, taking the name of St Paul in vain is generally regarded as one of the sins which lead to somebody being bitten by (his) spiders. [33]

De Martino adds that most of the dancers converse with an imaginary voice, that of the spider or that of Saint Paul, with the distinction between the two not always clear. [34]

One male dancer, himself bitten of course by a spider, spoke with Saint Paul, whom only he could see or hear, during the pauses between dances.

“The voice of the saint, said Pietro, came to his ears as if from outside, but was not as clear as those of other people”. [35]

I was very much struck by the dancer Carnela’s account of having encountered Saint Paul in a dream.

“She dreamed of a great green meadow across which there came forward towards her a young man with a white beard, dressed in green with a red cape. Carnela at once recognised Saint Paul and wasted no time in asking him to cure her”. [36]

When you add in the fact that she then dreamed of water surging forth abundantly from the earth, [37] I am very much reminded of Khidr, that nature divinity indigenous to the Middle East to which southern Italy is so close.

As I wrote in The Green One, this white-bearded verdant saint is associated with sacred springs, fertilising rain, the greening of nature and the renewal of life. [38]

A strong connection with the universal human symbolism declaring our belonging to nature comes with the greenery used to decorate the scene of the ritual dancing, [39] as in Cornwall, [40] Lakash, [41] Albania, Croatia, Russia, Romania, Austria, Germany, [42] and just about everywhere else!

I will conclude by once again stressing that our belonging to nature is real and permanent.

Each one of us is aware of it deep down inside, beneath all the soul-smothering layers of industrial conditioning.

Although its ritual manifestations have often been snuffed out over the centuries and its spirituality derided and proscribed, its essence, because rooted in reality, lives on.

This innate nature-awareness is born again with every child who arrives in this world and, despite our life-denying overlords’ sinister efforts, will never be eradicated.

[1] Ernesto de Martino, La Terre du remords (Terra de rimorso), trans. Claude Poncet (Le Plessis-Robinson: Institut Synthélabo, 1999), p. 16. Translations from the French edition are my own. All following page references are to this work, unless otherwise stated.

[2] p. 45.

[3] Paul Cudenec, ‘Rooted in our living world’. https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/06/23/rooted-in-our-living-world/

[4] p. 53.

[5] pp. 106-07.

[6] p. 55.

[7] p. 209.

[8] p. 319.

[9] p. 78.

[10] p. 79.

[11] p. 80.

[12] pp. 165-66.

[13] p. 113.

[14] p. 117.

[15] A. Kircher, Magnes sive de arte magnetica libri tres (Rome: 1641), p. 770, cit. p. 180.

[16] pp. 182-83.

[17] p. 117.

[18] p. 309.

[19] Ludwig Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, 6th edition (Bonn: Bouvier Verlag Herbert Grundmann, 1972), p. 1054, cit. Paul Bishop, Ludwig Klages and the Philosophy of Life: A Vitalist Toolkit (Abingdon/New York: Routledge, 2018), p. 131.

See Paul Cudenec, The Global Gang Running Our World and Ruining Our Lives (2025), pp. 89-90.

https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/the-global-gang-web.pdf

[20] Ludwig Klages, Vom Wesen des Bewusstseins, Sämtliche Werke 3, ed. Ernst Frauchiger, Gerhard Funke, Karl J. Groffmann, Robert Heiss and Hans Eggert Schröder, 9 vols (Bonn: Bouvier, 1964

1992) pp. 391-92, cit. Bishop, p. 135.

[21] A. Kircher, Musurgia universalis sive ars magna consoni et dissoni, (Rome: 1650), II, p. 222, cit. p. 203.

[22] p. 202.

[23] p. 235.

[24] Paul Cudenec, ‘Channelling the spirit of life’. https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/06/02/channelling-the-spirit-of-life/

[25] pp. 279-80.

[26] https://winteroak.org.uk/2025/06/27/our-sacred-belonging/

[27] p. 313.

[28] pp. 250-51.

[29] p. 251.

[30] p. 256.

[31] Paul Cudenec, ‘The spirit of Sophia’, The Global Gang, pp. 38-67.

[32] p. 93.

[33] p. 103.

[34] pp. 118-19.

[35] p. 96.

[36] p. 115.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Paul Cudenec, The Green One (2017), pp. 105-115.

https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/the-green-one-1.pdf

[39] p. 161.

[40] Cudenec, ‘Channelling the spirit of life’.

[41] Cudenec, ‘Rooted in our living world’.

[42] Cudenec, The Green One, pp. 127-128.

Kircher: “That the spiders take pleasure from a certain colour is proven by the fact that if you place them on various coloured surfaces, they choose that of a similar colour to their own”. — Triggered, I suspect, by an instinct for camouflage.

“This innate nature-awareness is born again with every child who arrives in this world and, despite our life-denying overlords’ sinister efforts, will never be eradicated.” — Which is indeed, at the very heart of our “life-denying overlords’” love of /obsession with, transhumanism.

Spiders themselves can be infected by parasites which compel the host to dance to the parasite's tune.

The Zatypota species of parasitic wasp infests the social Anelosimus eximius spider, of the Ecquadorian Amazon. It lays eggs on the abdomen of the spider. When the larva hatches, it then feeds upon its host’s blood, growing until it subsumes much of the spider’s body. As it feeds, it injects a brain-altering hormone into the spider’s blood stream. This hormone hijacks the host’s brain and behaviour, compelling it to abandon its colony and build a cocoon web. The parasitic wasp larva then devours what is left of its host and slithers into the cocoon which it uses an incubator. After it emerges as a mature wasp, the cycle begins anew.

Call Alice

When she was just small

https://hughboone.substack.com/p/covax-through-the-looking-glass-part-6