Collaboration & Denial

[I read the article here)

The French state is apparently very keen to ensure accurate memories of traumatic historical events – since 1990 “the denial of the existence of crimes against humanity”, such as the mass extermination of Jews during the Second World War, has been a criminal offence. [1]

But, for reasons which are perhaps best explained by Jacob Cohen in his 2010 book Le Printemps des Sayanim [2] or by Jean Bouvier in his 1983 tome Les Rothschild, [3] this same rigorous commitment to truth seems sometimes to waver, depending on the identity of those regarded as having committed such crimes.

A new law on the way through – known as the Loi Yadan because it is being pushed by Zio-Macronist government minister Caroline Yadan – sets out to criminalise criticism of Israel and Zionism. [4]

Based on the absurd IHRA expansion of the definition of “anti-semitism” it aims in particular to penalise any suggestion that Israel’s actions are similar to those of Nazi Germany. [5]

This therefore seems like an appropriate moment to write about a 1980 book by Maurice Rajsfus on elite Jewish collaboration in the WW2 deaths of what he estimates at 75,000 Jews living in the country. [6]

As Pierre Vidal-Naquet says in the preface, Rajsfus comes to the same conclusion as Hannah Arendt, whose work I recently discussed [7] – namely that “Hitler’s extermination policy was facilitated by the co-operation of a small number of Jews – notably the ruling class”. [8]

Rajsfus (1928-2020), who was Jewish and both of whose parents died at Auschwitz, [9] notes a definite reluctance to face the terrible truth revealed by his meticulous combing of archived papers.

He insists: “You only have to read the documents that I cite in order to understand that the Jewish masses in France were at the same time victims of the Nazis and of the Jewish ‘elites’ placed in power by the Nazis”. [10]

“In France everything possible was done to wipe from memory the attitude of UGIF [L’Union générale des Israélites de France, which is the focus of his research].

“It was then simply a question of purely and simply denying the facts that were held against them and, finally, manufacturing for them a halo of martyrdom and resistance”. [11]

This is one kind of “denial” that is not likely to be outlawed by a state currently headed by Emmanuel Macron, so close to the Rothschilds, those godfathers of Zionism.

Rajsfus writes, back in 1980: “Ever since we started this work, there has been no lack of warnings and disapproval. This is a taboo subject over which a veil has been drawn since the end of the war.

“This allowed the survivors of this adventure to return to the fold without their activity ever being exposed to the public. In 1945 we even saw these people ask the new authorities to silence those who wanted to shed light on this scandal.

“Almost 40 years later, members of the Jewish establishment in France (on the right and left), still consider that it is not good to describe the misdeeds of these elite figures under the Nazi occupation.

“‘Professional’ Jews were the most vehement in denouncing the publication of this book, judging that this could only do harm to the Jewish community as a whole, at a time when anti-semitic activities are sometimes regaining a certain vigour”. [12]

Funny how, at any given historical moment, “anti-semitism” always seems to be alarmingly on the rise!

The situation of Jews in France was very different from that of those in Poland, who were also betrayed by their leaders under Nazi occupation.

In 1939, says Rajsfus (pictured), there were a little over 350,000 of them in France, 200,000 of whom lived in the Paris area and the rest in Marseilles, Lyons, Alsace, Bordeaux and elsewhere. [13]

They were not separate from the French population in the way that Jews were in Poland and neither were they a homogenous entity, the longstanding Jewish population having been joined by large numbers of immigrants from Eastern Europe – including Rajsfus’s family – who did not belong to the same social class.

He says that by 1939, what he calls “French Jews” were a minority in the Jewish population but a clear majority amongst Jewish bankers. [14]

Some of these French Jews, often very well-off, were concerned that the presence in France of significant numbers of working-class Jewish immigrants could stoke anti-semitism and threaten their own status.

Even before the Nazi occupation, it was clear that they had an affiliation with the political “right”, even the “far right”. And, Rajsfus notes, in June and July 1940 it was a Jewish intellectual, Emmanuel Berl, who wrote the first speeches of Maréchal Philippe Pétain, who ran the southern Vichy regime in collaboration with the Nazis. [15]

He describes the outlook of the Consistoire central israélite de France, the main body representing the Jewish faith.

He says this was very much dominated by the Rothschild family [16] – indeed, I see that when war broke out the president of the central Consistoire was Édouard de Rothschild and the president of the Paris Consistoire was his cousin Robert de Rothschild. [17]

Rajsfus continues: “The most conspicuous spokespeople for the French Jews (directors of the Consistoire, even rabbis), were not shy about associating with the men of order of the time and, in particular, the Croix-du-feu of Colonel [François] de la Rocque”. [18]

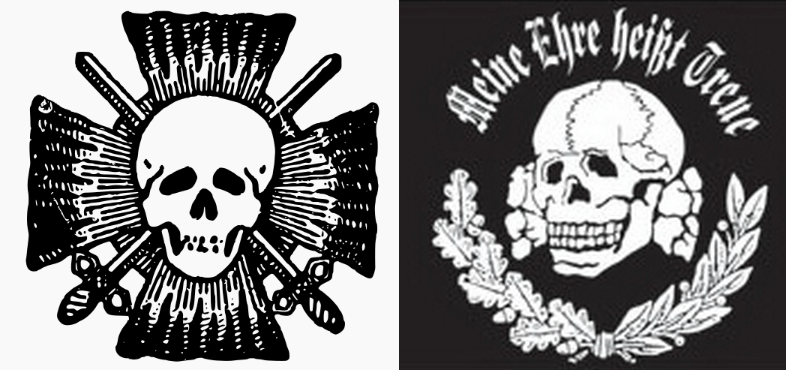

This organisation, banned by the Front populaire government in 1936, was originally an ex-servicemen’s group but is considered by some to have been “fascist” – its death-head logo (left) certainly resembles the Nazi SS Totenkopf (right). [19]

Rajsfus explains that, until the ban, the Consistoire regularly invited this group to take part in “patriotic” ceremonies at the synagogue in rue de la Victoire, Paris.

“These were not casual encounters and we saw Jewish ex-servicemen taking part in the fascist riot of February 6 1934”. [20]

“Moreover, it was with the blessing of the president of the Paris Consistoire, Robert de Rothschild, that in June 1934 the Union patriotique des Français israélites was created…

“Several representatives of the French Jewish community in Paris featured among the leadership of the Parisian section of the Croix-du-Feu.

“Attending a Croix-du-Feu meeting in Paris, Rabbi Jacob Kaplan of the rue de la Victoire synagogue went so far as to declare: ‘Without having the honour of belonging to your association, I cannot help considering myself to be one of you’”. [21]

Kaplan survived the war and went on to become Chief Rabbi of Paris from 1950 to 1980 and Chief Rabbi of France from 1955 to 1980. [22]

Rajsfus explains that while Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe were often Zionists, they tended to embrace a left-wing variety based on the Kibbutz movement.

French Jews, on the other hand, “were more attracted by the far-right doctrines of Vladimir Jabotinski’s ‘revisionist Zionists’ that left-wing activists regarded as actually fascist.

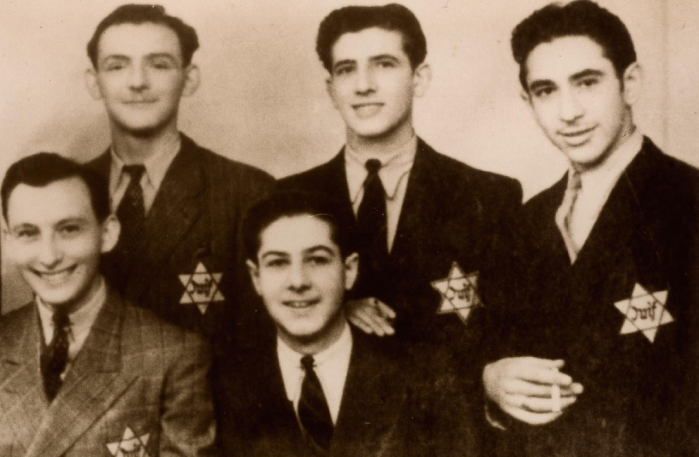

“At the time, groups following Jabotinksi (pictured) even paraded in brown shirts. Hence the label Braune Yidden (Brown Jews) which was taken up again several years later to describe UGIF’s leaders”. [23]

Rajsfus does not mince his words in describing this latter body, stressing: “UGIF was entirely manufactured by the Gestapo”. [24]

The same view was held by Jewish members of the Resistance who attacked its offices in Marseilles and Lyons in 1944, burning the lists of Jewish adults and children that it had so usefully compiled. [25]

The small numbers of Jewish Resistance fighters were, says Rajsfus “stigmatised right until the end by UGIF’s leaders, when they were not purely and simply betrayed to the Nazis as was undoubtedly the case on certain occasions”. [26]

The Resistance bulletin Notre voix (‘Our Voice’) declared in June 1943 that all Jews “should treat UGIF as a branch of the Gestapo”. [27]

A priority everywhere for Nazi occupiers was to set up Jewish-run official bodies, on the model of the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland which, according to the Jewish Virtual Library “enabled the Nazis to implement many of their deadliest orders without much publicity”. [28]

The Judenräte, Jewish Communes, used for this purpose in Poland, as I describe in ‘The gangsters and the ghetto’, were not appropriate for France. [29]

Says Rajsfus: “What was relatively easy to create in Poland or in Lithuania where there were lots of ghettos was not really exportable to France.

“This was for a number of reasons: there was not one community, but several, not to mention those individuals whose sole aim was assimilation”. [30]

Better for Western European countries was something like the L’Association des Juifs de Belgique (‘Association of Belgian Jews’), which Rajsfus describes as “a masterpiece of its kind”.

He explains: “It was the AJB that had to draw up the list of Jews in Belgium and which was charged with issuing a command to every family telling them to report to the place of internment prepared by the Nazis.

“This was presented in the form of a work order. 30,000 Belgian Jews were thus gathered at the Dussin de Malines barracks before being deported to the death camps”. [31]

The initial organisation set up by the Nazis in France in January 1941, UGIF’s precursor, was the Comité de coordination des Oeuvres de bienfaisance juives du Grand-Paris (‘Coordination Committee of Jewish Charitable Works of Greater Paris’).

After 4,000 Eastern European Jews were that same year rounded up by the French police and placed in camps at Pithiviers (pictured) and Beaune-la-Rolande, their wives sought support from this supposedly charitable Jewish organisation.

But the Comité was run by a certain Léo Israél Israélowicz who, along with fellow Austrian Jew Wilhelm Biberstein, had been sent to Paris from Vienna by none other than Adolf Eichmann, the SS officer whose ambiguous relationship with Zionism I explored in ‘A Joint embrace of evil’. [I was informed in the comments section of that article that, according to Hennecke Kardel, Eichmann was in fact Jewish].

Israélowicz went on to lead UGIF’s liaison with the Gestapo, before being killed in disputed circumstances in 1943 – possibly by a fellow Jew who knew of his role as a Nazi collaborator. [32]

Unsurprisingly, he was not of much help to the protesting women, initially telling them that their imprisoned menfolk were “martyrs” and speaking of their “sacrifice”. [33]

The next time that the women visited him, it was with the angry conviction that his organisation was complicit in the men’s fate and that the “rich Jews” were trading these lives for their own safety. [34]

It seems that at some point Israélowicz laid a hand on one of the women and all hell broke loose. He ran off to barricade himself in his office, where his first instinct was to call SS captain Theo Dannecker (pictured) for help! [35]

When the women turned up again the next week, Israélowicz called the police on them, prompting a massive 5,000-strong protest two days later, in the course of which one woman threatened to blow his house up. [36]

Rajsfus provides plenty of evidence of how the Comité and then UGIF worked hand in hand with the Nazi occupiers.

For instance, he writes: “On the morning of July 15 1942, UGIF members were summoned by pneumatic to the organisation’s offices in rue de la Bienfaisance, where its social services were based”. [37]

By way of explanation, the pneumatic post was a 250-mile network of delivery tubes that was still operational in Paris when Rajsfus was writing, closing only in 1984. [38]

He continues: “So what was the urgent task that required the sending of pneumatic letters? It was simply a matter of producing thousands of cardboard labels to which a string was attached. They looked strangely like the labels put around the necks of evacuated children in 1940.

“At UGIF HQ they had already been well aware, for several days, that massive raids were going to take place on July 16 and 17 and the labels were for the thousands of children who were to be separated from parents arrested and transported to the Vel’d’hiv [a stadium in Paris] and then to the camp at Beaune-la-Rolande before being deported to the East”. [39]

At the end of 1941 and on two further occasions, Chief Rabbi Isaïe Schwartz “urged Jews to submission under the pretext of loyalty to Judaism, when the first Nazi ordinances were imposed”, says Rajsfus. [40]

And the Comité’s Informations juives and then UGIF’s Bulletin, both edited by Eichmann’s faithful lackey Israélowicz, were used to relay Nazi messaging to the Jewish population.

Why would they have any reason to distrust “information” provided by their own community leaders?

These newsletters told readers that they must wear their yellow stars and obey the Nazi laws separating Jews from the rest of the population.

Rajsfus says that by the start of 1943 it was clear that UGIF was nothing but “an intermediary between the Nazis and the Jewish masses”. [41]

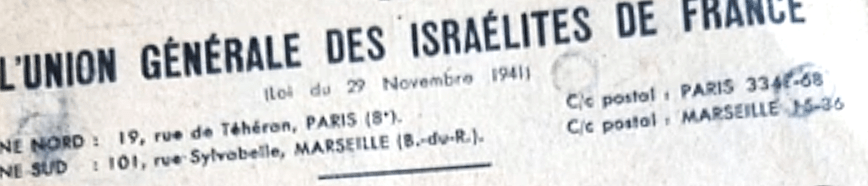

He says that in the Bulletin of February 1943 and subsequent issues could be seen a communiqué in large type with the heading “Avis important” – Important Notice.

This declared: “The German Authorities forbid all persons to raise any procedural matters or direct requests to their offices and services on behalf of a Jew.

“Only the Union générale des Israélites de France, 19 rue de Téhéran, Paris (service 14), is authorised to present to the occupying Authorities demands concerning Israelites”. [42]

Service 14 was the notorious Gestapo liaison service run by Israélowicz, who met with the Nazis on a literally daily basis. [43]

His UGIF Bulletin even warned Jews whose homes had been sealed by the Nazis not to try to get back in to rescue their possessions but to contact service 14 to follow the legal route.

Rajsfus rightly questions the motivation in advising Jews with illegal status – since their homes had been sealed – to get in touch with the Gestapo’s trusted intermediaries: “This looks a lot like the mousetrap technique”. [44]

A key role played by these collaborators was to herd Jews together so that they could be clearly identified.

Informations Juives told its readers in May 1941: “Openly aligning oneself with a community whose fate is harsh is undoubtedly less painful for the individual than refusing to perform this act and subsequently belonging nowhere, remaining isolated and unprotected in the midst of the whirlwind of events”. [45]

This is, of course, a complete inversion of the truth. The best recourse for any Jew in Nazi-occupied or Vichy-run wartime France would have been to melt quietly away into the general population until the danger had passed.

As in Poland, these Jewish collaborators sought to reassure the Jewish population that the Nazis were not planning anything untoward for them.

Rajsfus writes: “Throughout the occupation and even when, from 1943, it was obvious that the camps in the East were nothing but massive extermination factories, UGIF’s leaders, although well informed, refrained from making this situation clear.

“On the contrary, they explained that it was just a matter of going for work, of going to colonise the uncultivated land of central Europe”. [46]

UGIF’s Fernand Musnik wrote to one worried Jew in November 1942 that his organisation had received postcards from people deported to Birkenau concentration camp in Poland (pictured) and “the information given by the senders of these cards concerning the work, the food and the situation in general is very satisfactory”. [47]

UGIF raised taxes for the Nazis, provided supplies for their armed forces and kept order for them, says Rajsfus, applying Nazi laws as rigidly as any German bureaucrat. [48]

He describes how Armand Katz, secretary general of UGIF in the northern zone, refused to help a Jew arrested in the east of France.

Katz wrote to a local UGIF delegate in December 1942: “Unfortunately, his case is undefendable before the occupation Authorities, the internee having taken off his star, he is thus in formal contravention of the Ordinances.

“Furthermore, he was arrested in a café or restaurant, where he was also formally forbidden to be”. [49]

Rajsfus remarks of UGIF’s abjectly deferent tone: “Every time they write or speak the word ‘Authorities’, it is with a sort of fear mixed with respect. The capital letter must never be forgotten, it is very important”. [50]

UGIF obeyed the Nazi order to draw up lists detailing all the Jewish families living in Nazi-occupied northern France and in the “free” Vichy-run zone in the south. [51]

This clearly amounts to collaboration in the rounding-up of the Jewish population and their deportation to the camps.

How could the Nazis ever have managed it without UGIF’s help?

Victims even included 50 members of UGIF’s staff who had been made redundant and were then sent to the camps.

Rajsfus says UGIF knew full what would happen to them without their employed status and uttered not a single word in protest.

Moreover, the French authorities had passed to the SS a list of the employees made redundant, including their home addresses – “this list could only have come from UGIF”. [52]

UGIF’s role in the detention and deportation of Jewish children is particularly controversial.

While its defenders claim it carried out valuable work in this respect, Rajsfus insists: “UGIF did not save children. We can even say that it lost them”. [53]

He refers to “the harmful role it played in the arrests of children” [54] and points out that it “objectively co-operated with the Nazis to the point of giving them complete lists of children staying in certain houses in the Paris area”. [55]

He cites another “Important Notice” printed in several editions of UGIF’s Bulletin following the mass raids of July 1942.

Here, UGIF announced that it was compiling a file of all the Jewish children whose parents had been arrested.

“If these children have been taken up by a private body or by individual families and you have knowledge of this, we ask that you let us know immediately since it has already been brought to our attention that some children have been lost”. [56]

Rajsfus says this UGIF notice “is laden with menace because it prefigures the gathering together of these ‘lost children’ in houses where they were under close surveillance and where the Nazis could easily come to raid them”. [57]

“In fact all the houses for children run by UGIF in the Paris area were raided, sometimes in the presence of their personnel.

“In the case of the Lamarck centre which, after an initial raid at the start of 1944 was moved to rue Secrétan, all the children were arrested and deported”. [58]

The direct nature of UGIF’s collaboration with the Nazis is, quite frankly, shocking.

One document unearthed by Rajsfus is an instruction to its social assistant Berthe Libers (pictured) that she submitted to a court case in 1947.

It reads: “By order of the SS Obersturmführer, Mlle Libers must go to Championnet where she will find the children Moskowitz Ida et Moskowitz Georgette and take them to the Lamarck centre”. [59]

UGIF actively prevented the Resistance from rescuing children from its Nazi-approved prison-houses.

Irène Cahen, a UGIF social assistant, stated in September 1944 (when the Nazis had left Paris): “After the Antiquaille affair, when six children were abducted by the Resistance, I went myself to alert the Gestapo”. [60] She declared proudly: “I never thought of helping a single child escape. I had to hand them to the Gestapo”. [61]

At the same time as working closely with the Nazis, UGIF was, of course, enmeshed in Zionist networks. This aspect of its activities was more obvious in the southern zone, where it was safer, until the Germans took over at the end of 1942, to bring Jewish youth together in one place.

Here there were agricultural schools, under the aegis of UGIF, which trained youngsters “to become future farm workers in Palestine”. [62]

Many were from non-practising families, but were now schooled in Jewish religion and tradition, and taught Hebrew, in preparation for their future role in the as-yet non-existent Israeli state. Rajsfus comments: “Young Jews had to be saved, but so as to turn them into fervent Zionists”. [63]

Working closely with UGIF, openly in the south, were Les Eclaireurs Israélites de France, EIF. “It is no coincidence that on UGIF’s First Council of Administration sat two leading directors of EIF: Robert Gamzon in the south and Fernand Musnik in the north”. [64]

“The directors and management of EIF were Zionists. Indeed this organisation was founded in the 1930s to reinforce the implantation of the Zionist movement in France. To draw in young people, the organisation was modelled on the French scouting movement”. [65]

UGIF also worked hand-in-glove with international Zionist “humanitarian” body the American Joint Distribution Committee.

As I wrote in ‘A Joint embrace of evil’, this Rothschild-linked organisation had been one of the Zionist groups that had blocked moves in 1938 to facilitate mass Jewish emigration from the Third Reich.

American historian Zosa Szajkowski revealed in 1947 that UGIF had acted as a channel for “illegal assistance” reaching France from The Joint. [66]

Because of this “considerable aid from The Joint”, UGIF in the south was not compelled to follow the example of the northern section and “fund their budget with money coming from the expropriation of Jewish establishments”. [67]

Another report appended by Rajsfus refers to a web of Zionist fronts in wartime France “and behind them, to finance them, the American Joint, of which certain directors were ‘social inspectors’ at UGIF”. [68]

The author also takes a look at the “interesting” role of Jules Jefroykin (pictured), The Joint’s delegate to France, a “character who always worked in the shadows and with efficiency”. [69]

He says it is worth noting the importance that UGIF placed on Jefroykin and The Joint, which was based first in Marseilles and then in Nice.

“Since the entry of the USA into the war against Germany in December 1941, Jefroykin had benefited from a real diplomatic protection which facilitated his activities and contacts”. [70]

Rajsfus says he “was able to collect money (a lot of money, it would seem), from very wealthy individuals sheltering in the south”. [71]

But this money was not to help the Resistance, even the Jewish Resistance, but was purely for “charitable works”.

“The Joint, as an American organisation, was forbidden by the State Department to send money to Europe, because US leaders considered that any financial support could contribute indirectly to the Nazi war effort if it was invested in occupied territories.

“At the same time, money collected on the spot in the name of The Joint (which opened many a door) had to be spent honourably, in other words charitably”. [72]

“What did this actually amount to? Jefroykin chose the charitable works to support and, in the process, UGIF in the south sometimes reaped royal financial benefits”. [73]

The ajpn website says that “significant funding” was provided by The Joint to UGIF’s Juliette Stern (pictured). [74]

It presents her as a member of the Resistance, who saved Jewish children from the Nazis, but a rather different picture is painted in the testimony of a genuine Resistance member Fréderic Léon, shared by Rajsfus.

He explains that in early 1944 most of the children in UGIF homes had been rounded up and taken to the Drancy holding camp, but 28 children at its house in Neuilly had somehow been overlooked by the Nazis.

He says that, “for once”, UGIF’s Georges Edinger took the initiative of ordering the children to be dispersed and hidden in whatever way possible, before the Nazis turned up.

When Stern found out what was happening she leapt into action, Léon explains: “She told M. Edinger of the great danger that was being created for UGIF’s Council, its officials and even for all the Jews of Paris…

“She did not want to run these risks at any price and the children should be brought back immediately. M. Edinger backed down, Mme Stern being (we don’t know why, or perhaps we know all too well) all-powerful on the UGIF Council”. [75]

As the children were brought back to the house, Edinger became anxious that this was not happening as quickly as Stern would have hoped and “sent a member of the UGIF Council, M. Dreyfus, armed with a typed list, in three copies, to monitor, and if possible to speed up, the return of the children.

“At this stage, only 20 or so had been brought back and the others had disappeared: the people to whom they had been entrusted, probably seeing what was going to happen, were refusing to hand them over.

“Trembling with fear, M. Dreyfus went back to the rue de Téhéran [UGIF offices] to report on his mission, bringing back the lists”. [76]

A few hours later a coach arrived for the children, “escorted by two Jewish policemen attached to the Gestapo at Drancy”.

A roll call was made, the police having one of the typed lists, and the children were taken to the Drancy camp, accompanied by two women.

Once at the camp, one of these women, Hélène Lob, saw on camp commandant Alois Brünner’s desk “one of the typed lists: while at the other houses, the children had been taken without any list of names being asked for and the question is raised as to why a list of the children was delivered to Brünner?

“Why did the policeman with the coach possess one and was the third in the hands of M. Edinger or in those of Mme Stern? Brünner had certainly not asked for a list because he had not asked for that at the other houses.

“We have to ask whether they were sent to him as a matter of course? By whom? By M. Edinger or Mme Stern? The two together, perhaps?” [77]

I was struck by Léon’s aside about Stern “being (we don’t know why, or perhaps we know all too well) all-powerful on the UGIF Council” and by his description of her as being “a very important” figure [78] in UGIF.

I had a look at her connections and found that she was a major figure in the Zionist movement in France. She had already been involved in the Zionist colonisation of Palestine in the early 1930s, set up the Union des femmes juives de France pour la Palestine, was president of the French branch of WIZO, the Women’s International Zionist Organization, and became part of its global leadership. [79]

On her death in 1963, Walter Eytan, the Israeli Ambassador to France, praised her “exemplary devotion to Israel, and Zionism, particularly to Jewish children”. [80]

During the war, Stern received heavy funding not just from The Joint, but also from the KKL (Keren Kayemet Leisraël) better known in English as the Jewish National Fund. [81]

This body was created at the fifth Zionist Congress at Basel, Switzerland, in 1901 and today boasts that its “Blue Box” fundraising scheme “built the State of Israel” by encouraging people to help Zionists “reclaim the Land of Israel and aid Jewish immigration there”. [82]

Its website tells us, interestingly, that in October 1922, its Paris and Strasbourg committees published together an illustrated pocket almanach for the Jewish year, which featured portraits of “benefactors of Jewish Palestine” including Edmond de Rothschild. [83]

Not so coincidentally, the ajpn website identifies Stern as having been part of the “Fondation de Rothschild” (Rothschild Foundation) network in wartime France. [84]

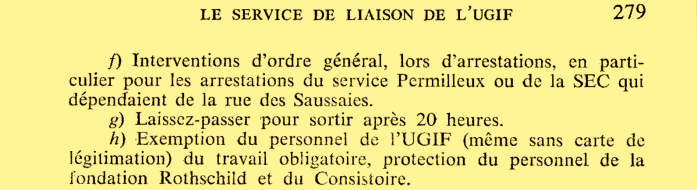

This organisation is also mentioned in the testimony, presented by Rajsfus, of Kurt Schendel, a Jewish lawyer and businessman originally from Berlin, who took over from Israélowicz as UGIF’s Gestapo liaison officer, performing the role from August 1943 to August 1944. [85]

On September 4 1943 he reported on his latest meeting at Gestapo HQ in the rue des Saussaies, Paris.

Item ‘h’ on the matters discussed was “Exemption of UGIF personnel (even without identification card) from compulsory work, protection of the personnel of the Rothschild Foundation and of the Consistoire”. [86]

On the basis of the history that is served up to us today, it would appear totally incomprehensible, even impossible, that a Foundation run by a Jewish banking dynasty, and the Jewish religious body which it dominated, should have been afforded special protection by the Gestapo!

But, as my regular readers will know full well, the truth of the matter is very different.

The reason why the Yadan Law is being pushed through in France today is undoubtedly because there really are strong links between Nazism and Zionism that are highly inconvenient for the official narrative.

We now have plenty of solid historical facts to confirm these connections, as I have been doing my best to set out in recent articles.

But sometimes we can intuitively grasp the link by catching sight of a certain chillingly inhuman outlook – totally alien to normal people – that is shared by the two monstrous ideologies.

A shudder of recognition ran down my spine when I read the account of how, in July 1944, Brünner, commandant of the Drancy camp, refused to spare Jewish children’s lives because “these children were future terrorists”. [87]

[1] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loi_Gayssot

[2] See Paul Cudenec, ‘The stench of the system: sayanim’, https://winteroak.org.uk/2024/11/04/the-stench-of-the-system-sayanim/

[3] See Paul Cudenec, Enemies of the people: The Rothschilds and their corrupt global empire (2022), https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/enemiesofthepeopleol.pdf

[4] https://www.jns.org/female-jewish-french-parliamentarian-my-goal-is-to-eradicate-antisemitism/

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caroline_Yadan

[5] https://blogs.mediapart.fr/collectif-dorganisations-contre-la-loi-yadan/blog/100126/loi-yadan-non-une-police-de-la-pensee

[6] Maurice Rajsfus, Des Juifs dans la Collaboration: L’UGIF (1941-1944) (Paris: Etudes et Documentation Internationales, 1980), p. 391. All translations are my own and all subsequent page references are to this work, unless otherwise stated.

[7] Paul Cudenec, ‘A Joint embrace of evil’, https://winteroak.org.uk/2026/01/28/a-joint-embrace-of-evil/

[8] Pierre Vidal-Naquet, Préface, p. 11.

[9] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maurice_Rajsfus

[10] p. 389.

[11] p. 336.

[12] pp. 38-39.

[13] p. 28.

[14] p. 29.

[15] p. 50.

[16] p. 31.

[17] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consistoire_central_isra%C3%A9lite_de_France

[18] p. 32.

[19] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Croix-de-Feu

[20] pp. 32-33.

[21] L’Univers israélite, March 23 1934, cit. p. 33.

[22] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacob_Kaplan

[23] p. 34.

[24] pp. 47-48.

[25] p. 298 & p. 302.

[26] p. 392.

[27] Notre voix, organ of the Rassemblement des Juifs contre le fascisme oppresseur, June 1 1943, in La Presse antiraciste sous l’occupation (1950), cit. p. 295.

[28] https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/reichsvereinigung, see Paul Cudenec, ‘The Zionist regime was a Nazi golem’, https://winteroak.org.uk/2026/01/08/the-acorn-108/#2

[29] https://winteroak.org.uk/2026/01/23/the-gangsters-and-the-ghetto/

[30] p. 44.

[31] p. 45.

[32] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%C3%A9o_Isra%C3%A9lowicz

[33] Z. Szajkowski, ‘A Propos des manifestations des femmes d’internés au siège du Comité de coordination des Oeuvres de bienfaisance’, Analytical Franco-Jewish Gazetteer 1939-1945 (1966), Archives Yivo, New York, cit. p. 56.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Szajkowski, cit. p. 58.

[37] p. 54.

[38] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poste_pneumatique_de_Paris

[39] p. 54.

[40] p. 92.

[41] p. 162.

[42] Ibid.

[43] pp. 266-67.

[44] p. 289.

[45] Informations Juives, No 3, May 1 1941 cit. p. 82.

[46] p. 391.

[47] Centre de documentation juive contemporaine (CDJC)-CDLXV, cit. p. 153.

[48] p. 146 & p. 132.

[49] CDJC-CDXXIV, 2, cit. p. 152.

[50] p. 196.

[51] pp. 130-31 & p. 133.

[52] p. 161.

[53] p. 237.

[54] p. 248.

[55] p. 234.

[56] CDJC-XLVII, 27, cit. p. 238.

[57] p. 238.

[58] p. 239.

[59] CDJC-LXXIV, 12, pp. 100-104, cit. p. 252.

[60] CDJC-XXVIII 3-28, cit. p. 254.

[61] CDJC-XXVIII 3-28, cit. p. 255.

[62] p. 232.

[63] Ibid.

[64] p. 236.

[65] p. 235.

[66] Zosa Szajkowski, L’organisation de l’UGIF en France pendant l’occupation, cit. p. 370.

[67] Szajkowski, cit. pp. 370-71.

[68] ‘Faut-il dissoudre l’UGIF: Procès-verbal des discussions de la Commission Meiss, Grinberg, Adamitz, Geissmann, cit. pp. 374-75

[69] p. 168.

[70] p. 169.

[71] Ibid.

[72] p. 169.

[73] p. 170.

[74] https://web.archive.org/web/20190918142908/https://www.ajpn.org/personne-8226.html

[75] p. 259.

[76] p. 260.

[77] Ibid.

[78] p. 258.

[79] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juliette_Stern

[80] https://www.jta.org/archive/juliette-stern-ex-president-of-wizo-in-france-dies-in-paris-was-70

[81] https://web.archive.org/web/20190918142908/https://www.ajpn.org/personne-8226.html

[82] https://www.kkl.fr/histoire-kkl-de-france/

https://www.kkl.fr/la-boite-bleue-2/

[83] https://www.kkl.fr/histoire-kkl-de-france/

[84] https://web.archive.org/web/20190918142908/https://www.ajpn.org/personne-8226.html

[85] p. 274.

[86] Dr Kurt Schendel, CDJC-CCXXI, 26, cit. p. 279.

[87] Schendel, CDJC-CCXXI, 27, cit. p. 322.

Once again, Paul shines a hard, necessary light on Zionism—not as an abstract ideology, but as a lived historical machinery with blood on its hands. What makes this essay so unsettling is not polemic, but documentation: names, institutions, archives, and testimonies that the official memory industry works tirelessly to keep out of view.

This isn’t “denial.” It’s the opposite—refusing selective amnesia. When states criminalize comparison and outlaw inquiry, it’s usually because the record is already damning. Rajsfus did the work decades ago; you’re reminding us why it still matters.

History doesn’t become sacred by decree. It becomes dangerous when it’s fenced off.

Yet more important joining of dots … thanks!

“The reason why the Yadan Law is being pushed through in France today is undoubtedly because there really are strong links between Nazism and Zionism that are highly inconvenient for the official narrative.” — No doubt!

BTW, those pneumatic delivery tubes look like something out of Brazil (the movie).