[A new profile I have just written for the organic radicals site]

“We must be governed by the guide within rather than by the opinions of men”

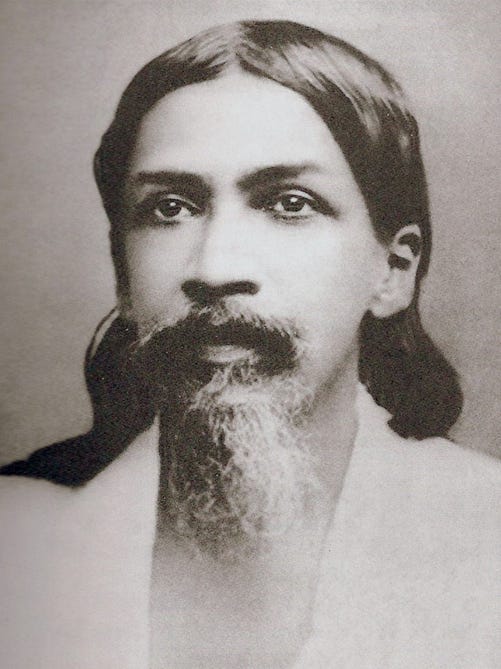

Sri Aurobindo (1872-1950) was in many ways the epitome of an organic radical inspiration.

On the one hand, he was a fiercely determined opponent of the global imperialist system, like Mohandas Gandhi, Bharatan Kumarappa and J.C. Kumarappa serving time in prison for his resistance to the British occupation of India.

On the other hand, he was a fine metaphysician, whose teaching did not steer people away from engagement with the world, as is too often the case, but instead stressed the spiritual imperative of using our physical existence for higher good.

Aurobindo played an important role in the struggle for swaraj, self-rule, and, before being imprisoned for a year in 1908, he edited a daily nationalist newspaper, Bande Mataram, which has been said to have “changed the political thought of India”. [1]

Mocking his “moderate” opponents, who referred to his own movement as “extremist”, he wrote: “To wish for our eternal serfdom is prudence and peacefulness. To think ourselves irremediably unfit is wisdom and moderation. To imagine ourselves a nation is madness. To love our country is superstition. To work for its emancipation is treason. To harbour any such sentiment is sedition”. [2]

The servile mental condition of so many educated Indians appalled him: “There is no longer any room in the Government schools for any but slaves and the sons of slaves”. [3]

And he declared: “If we are indeed to renovate our country, we must no longer hold out supplicating hands to the English Parliament, like an infant crying to its nurse for a toy, but must recognise the hard truth that every nation must beat out its own path to salvation with pain and difficulty, and not rely on the tutelage of another”. [4]

The sheer brutality of the British occupation angered him: “The Romans created a desert and called the result peace; the British in India have destroyed the spirit and manhood of the people and call the result law and order”. [5]

But his call for “popular freedom” [6] for Indians was also born of his keen awareness that the occupiers were operating on behalf of commercial interests and “employ Indian labour, not out of desire for India’s good, but because it is cheap”. [7]

He added that “exploitation of India by the British merchant” was the principal reason for bureaucratic colonial control. [8]

He identified a “a radical and congenital evil” at work: “The huge price India has to pay England for the inestimable privilege of being ruled by Englishmen is a small thing compared with the murderous drain by which we purchase the more exquisite privilege of being exploited by British capital”. [9]

Having grown up in industrial capitalist England, Aurobindo had there experienced at first hand “social degradation and an entire absence of the cohesive principle”. [10]

He approvingly referred to English poet and cultural critic Matthew Arnold’s description of this “modernised” and thus debased society as consisting of an aristocracy materialized, a middle class vulgarised and a lower class brutalized. [11]

Aurobindo then expanded on this analysis, at eloquent length.

“We may perhaps realize the nature of that unsounder aspect, if we amplify Matthew Arnold’s phrase: — an aristocracy no longer possessed of the imposing nobility of mind, the proud sense of honour, the striking preeminence of faculty, which are the saving graces — nay, which are the very life-breath of an aristocracy; debased moreover by the pursuit, through concession to all that is gross and ignoble in the English mind, of gross and ignoble ends: — a middle class inaccessible to the influence of high and refining ideas, and prone to rate everything even in the noblest departments of life, at a commercial valuation: — and a lower class equally without any germ of high ideas, nay, without any ideas high or low; degraded in their worst failure to the crudest forms of vice, pauperism and crime, and in their highest attainment restricted to a life of unintelligent work relieved by brutalising pleasures”. [12]

In contrast to this lowness at the rotten heart of the empire of greed, Aurobindo wrote of the lofty values represented by India’s ancient civilization.

“India cannot perish, our race cannot become extinct, because among all the divisions of mankind it is to India that is reserved the highest and the most splendid destiny, the most essential to the future of the human race”. [13]

“Ours is the eternal land, the eternal people, the eternal religion, whose strength, greatness, holiness, may be overclouded but never, even for a moment, utterly cease”. [14]

In order to free India from the dark forces of the global money-power, Aurobindo urged India’s traditional spiritual warriors to come to the fore.

He said: “It is high time we abandoned the fat and comfortable selfish middle-class training we give to our youth and make a nearer approach to the physical and moral education of our old Kshatriyas or the Japanese Samurai”. [15]

“Politics is the work of the Kshatriya and it is the virtues of the Kshatriya we must develop if we are to be morally fit for freedom.

“But the first virtue of the Kshatriya is not to bow his neck to an unjust yoke but to protect his weak and suffering countrymen against the oppressor and welcome death in a just and righteous battle”. [16]

Although Aurobindo supported boycotts and parallel structures as a tactic, [17] he rejected the fetichisation of any particular form of resistance and favoured a flexible approach.

“Resistance may be of many kinds, — armed revolt, or aggressive resistance short of

armed revolt, or defensive resistance whether passive or active: the circumstances of the country and the nature of the despotism from which it seeks to escape must determine what form of resistance is best justified and most likely to be effective at the time or finally successful”. [18]

There were limits to passive resistance, he said, and the moment that physical coercion of the people was attempted, “active resistance becomes a duty”.

He continued: “If the instruments of the executive choose to disperse our meeting by breaking the heads of those present, the right of self-defence entitles us not merely to defend our heads but to retaliate on those of the head-breakers.

“For the myrmidons of the law have ceased then to be guardians of the peace and become breakers of the peace, rioters and not instruments of authority, and their uniform is no longer a bar to the right of self-defence”. [19]

Aurobindo continued to convey this outlook through the philosophy of Yoga which he developed in French-controlled Pondicherry during the second half of his life, alongside Mirra Alfassa (referred to as "The Mother").

Spiritual warriors, he said, can become “the channel in our mind and body for a divine action poured out freely upon the world”. [20]

Although this involved shedding the ego to become aware of universal belonging, the individual remained crucial, not just eventually as a physical tool for divine action but also as the means by which this gnosis might first be accessed.

“We must be governed by the guide within rather than by the opinions of men”, Aurobindo wrote. [21]

“Individualism is as necessary to the final perfection as the power behind the group-spirit; the stifling of the individual may well be the stifling of the god in man”, he warned.

“There is continually a danger that the exaggerated social pressure of the social mass by its heavy unenlightened mechanical weight may suppress or unduly discourage the free development of the individual spirit.

“For man in the individual can be more easily enlightened, conscious, open to clear influences; man in the mass is still obscure, half-conscious, ruled by universal forces that escape its mastery and its knowledge”. [22]

When the individual realised his power to channel and express the light of the universe, he could allow the life force which had always animated him to take on a new meaning as “an indispensable intermediary” [23] between above and below, said Aurobindo.

This was a way of enabling the highest truth to become present and active in the physical world.

Rather than suggesting that when we have become aware of our cosmic belonging we should withdraw from the “illusion” of the physical reality we have previously experienced, Aurobindo insisted that, on the contrary, we should return to the fray in a renewed form.

This was the very essence of his “integral and synthetic” form of Yoga, he said.

“An absolute liberty of experience and of the restatement of knowledge in new terms and new combinations is the condition of its self-formation.

“Seeking to embrace all life in itself, it is in the position not of a pilgrim following the highroad to his destination, but, to that extent at least, of a path-finder hewing his way through a virgin forest”. [24]

Video links: Sri Aurobindo: A New Dawn. An Inspirational Hand Painted Animation Film (28 mins), The Transformation: a documentary film on Sri Aurobindo (54 mins).

[1] https://web.archive.org/web/20150311184542/http://www.sriaurobindoashram.org/ashram/sriauro/life_sketch.php

[2] Bande Mataram, The Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 2002), p. 485.

[3] Bande Mataram, p. 113.

[4] Bande Mataram, p. 10.

[5] Bande Mataram, pp. 219-20.

[6] Bande Mataram, p. 140.

[7] Bande Mataram, p. 133.

[8] Bande Mataram, p. 222.

[9] Bande Mataram, p. 271.

[10] Bande Mataram, p. 42.

[11] Bande Mataram, pp. 32-33.

[12] Bande Mataram, p. 43.

[13] Bande Mataram, p. 84.

[14] Bande Mataram, p. 315.

[15] Bande Mataram, p. 223.

[16] Bande Mataram, p. 238.

[17] Bande Mataram, p. 300.

[18] Bande Mataram, p. 299.

[19] Bande Mataram, pp. 294-95.

[20] Sri Aurobindo, The Synthesis of Yoga (Pondicherrry, India: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1973), p. 43.

[21] Aurobindo, The Synthesis of Yoga, p. 316.

[22] Aurobindo, The Synthesis of Yoga, p. 185.

[23] Aurobindo, The Synthesis of Yoga, p. 162.

[24] Aurobindo, The Synthesis of Yoga, p. 50.

Thank you Paul, this is indeed a radical view of how spirituality and socio political activism can be combined. I spent years studying the theosophical teachings of Alice Bailey et al which was a useful foundation but also inevitably an imprisoning of the soul in idealism and platitudes. Sheltering in the belief that the pseudo altruism of the U N SDGs amongst other claptrap is going to save humanity from Evil. We need to have both 'the guile of the serpent and the innocence of dove' to understand what is really going on and do something about it in our own sphere of influence.

Great, inspiring. Now how do we translate this message into the reality of our lives lived in today's culture of algorithms, AI, reliance on social media which itself is muffling our voices? I could go on...My answer would be some form of warriorship which floats free of being hypnotized by little screens.