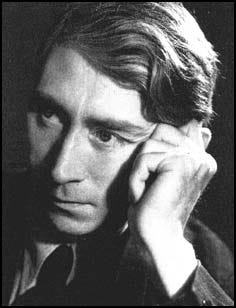

Today marks the 130th anniversary of the birth of Herbert Read, one of the thinkers who has most shaped my own political philosophy. This seems like an appropriate occasion on which to share the profile of him that I wrote for the organic radicals website. The film linked at the end is also well worth watching.

Herbert Read (1893-1968) was a prominent intellectual, poet and anarchist who, while championing modern British art, was strongly critical of modernity as a whole.

He was a strong supporter of the anarchist struggle in Spain, co-founded the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London and was a friend both of George Orwell and of Carl Jung, whose works he published and whose philosophy deeply influenced his mature thought.

Like Orwell, Read refused to let his work and activities be restricted by any external political line, insisting instead that “it is perfectly possible, even normal, to live a life of contradictions”. (1)

Read’s roots in rural Yorkshire meant he always had an affinity for nature and the countryside and a equal dislike for industry.

He despaired of living in what he termed “this foul industrial epoch”, (2) which, as he understood even then, was “a disaster that is likely to end in the extermination of humanity”. (3)

To find oneself living in such a nightmarish world obviously had a deep effect on one’s own state of mind and relationship to society. Declared Read: “Deep down my attitude is a protest against the fate that has made me a poet in an industrial age”. (4)

He said the modern poet did not write for fame nor for money, but to express his own bitterness at the disparity between “the ugliness of the world that is and the beauty of the world that might be”. (5)

He was trapped in a mechanical civilization, surrounded by steel cages and the futile voices of slaves, wrote Read. “To be part of civilization is to be part of its ugliness and haste and economic barbarism. It is to be a butterfly on the wheel. But a poet is born. He is born in spite of the civilization.

“When, therefore, he is born into this apathetic and hostile civilization, he will react in the only possible way, he will become the poet of his own spleen, the victim of his own frustrated sense of beauty, the prophet of despair”. (6)

Read saw clearly that industrialism was not just damaging to the natural environment and our physical health, but also to our ways of thinking and being, separating us from the very basis of our existence.

He wrote: “It is as simple as that: we have lost touch with things, lost the physical experience that comes from a direct contact with the organic processes of nature… We know it – instinctively we know it and walk like blind animals into a darker age than history has ever known”. (7)

As an art critic, Read had long been an enthusiast for modern art as an expression of the contemporary human spirit in all its disconnected and industrialised agony.

George Woodcock explains that he had hoped it would awake humanity to “growing threats to the quality and even the existence of human life, posed by unrestrained technological development”, but that Read had plunged into pessimism and “the emergence during the 1960’s of something approaching despair as he realizes that the new movements in painting, and particularly Pop Art, are themselves infected by the disintegration from which society as a whole is suffering”. (8)

In the face of this modern disintegration, Read developed an anarchist philosophy based on the idea of an alternative “organic society” (9). As he explained in The Philosophy of Anarchism: “There is an order in Nature, and the order of Society should be a reflection of it”. (10)

This natural organic order did not just exist in the physical structure of our world, Read realised, but also extended into our own minds – which were, after all, part of the selfsame physical natural reality.

Woodcock tells how Read had “an apocalyptic experience” of personally seeing the form of the ancient mandala, the symbol of the self as a psychic unity, appear spontaneously in modern children’s artwork.

At that point it struck him that there existed “a collective unconscious which is in harmony with nature but out of harmony with the world created by abstract systems and conceptual thought”. (11)

This collective entity, a living being on another level to that of the individual, obviously had to have some way of “thinking”, which was where poets, artists and the rest of human culture came in.

Read wrote about this process, and the way it fitted in perfectly with anarchist thinking, in his 1960 book The Forms of Things Unknown.

He explained: “We are to be kept alive in more than one sense: first as individuals, then as communities, and finally as a species. To keep ourselves alive as individuals we must practise mutual aid – that is to say, we must form communities.

“It now begins to look as though, in order to keep alive as communities, we must practise mutual aid at the community level, and eventually as a species. In order to practise mutual aid, we must communicate with one another…

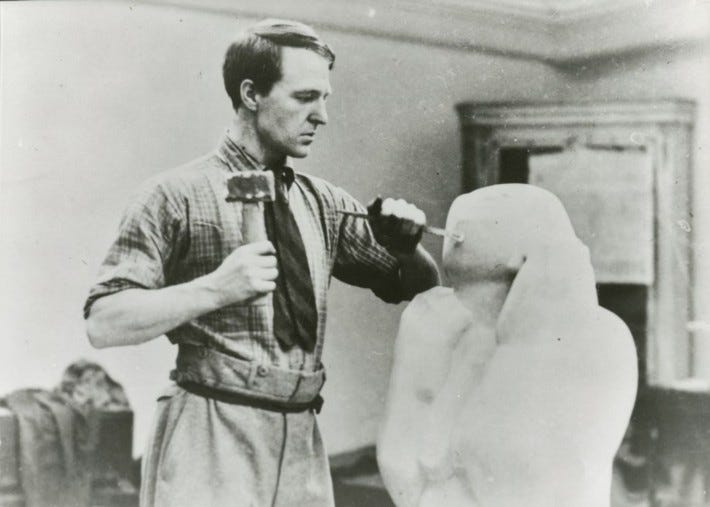

“The idea that words and symbols could be used positively, as synthetic structures that constitute effective modes of communication, does not seem to have occurred to our leading psychologists.

“Myth and ritual, poetry and drama, painting and sculpture – they have treated these creative achievements of mankind as so much grist for the analytical mill, but never as conceivably the disciplines by means of which mankind has kept itself mentally alert and therefore biologically vital”. (12)

For this communicative mutual aid to work, a society needed a living culture and “there is no culture unless an intimate relationship, on the level of instinct, exists between a people and its poets”. (13)

Read came to see the role of the individual artist within the context of the wider living cosmos of which she or he was part. “The artist is merely a medium, a channel, for forces that are impersonal”, (14) he wrote.

He depicted the spontaneous emergence of a psychic energy which, passing through the brain, expressed a variety of forms, “the typal forms of reality” (15) by which the universe existed. By giving them a shape and presence on the worldly plane, the artist therefore made these principles comprehensible to other human beings.

This organic functioning of human culture could never be possible under capitalism, where everything was reduced to the desire for money. But neither, saw Read, could it be possible under statist Marxism, which rejected any “mystical” anarchic ideas of organic collective entities.

He wrote: “It will be said that I am appealing to mystical entities, to idealistic notions which all good materialists reject. I do not deny it. What I do deny is that you can build any enduring society without some such mystical ethos.

“Such a statement will shock the Marxian socialist who, in spite of Marx’s warnings, is usually a naïve materialist. Marx’s theory – as I think he himself would have been the first to admit – was not a universal theory. It did not deal with all the facts of life – or dealt with some of them only in a very superficial way”. (16)

Read’s organic vision of life was relevant not just for society as a whole, but also for his own personal understanding of what it meant to be an individual human being, doomed to a mortality which some can only see as absurd.

He saw himself as a metaphorical leaf on a collective tree: “Deep down in my consciousness is the consciousness of a collective life, a life of which I am part and to which I contribute a minute but unique extension.

“When I die and fall, the tree remains, nourished to some small degree by my brief manifestations of life. Millions of leaves have preceded me and millions will follow me; the tree itself grows and endures”. (17)

As an anarchist, Read’s spirituality was not of the passive, quietist variety too commonplace today, as he was keen to stress.

He wrote: “Faith in the fundamental goodness of man; humility in the presence of natural laws; reason and mutual aid – these are the qualities that can save us.

“But they must be unified and vitalized by an insurrectionary passion, a flame in which all virtues are tempered and clarified, and brought to their most effective strength”. (18)

Video link: To Hell With Culture – a film about Herbert Read, art and anarchism (55 mins)

1. Herbert Read, cit. George Woodcock, Herbert Read: The Stream and the Source (Montreal/New York/London: Black Rose Books, 2008) p. 4.

2. Herbert Read, Poetry and Anarchism, cit. Woodcock, p. 214.

3. Read, cit. Woodcock, p. 232.

4. Read, cit. Woodcock, p. 206.

5. Herbert Read, Phases of English Poetry, cit. Woodcock, p. 70.

6. Ibid.

7. Herbert Read, The Contrary Experience, cit. Woodcock, p. 53.

8. Woodcock, p. 202.

9. Herbert Read, The Philosophy of Anarchism, cit. Woodcock, p. 197.

10. Read, The Philosophy of Anarchism, cit. Woodcock, p. 192.

11. Woodcock, p. 246.

12. Herbert Read, The Forms of Things Unknown: Essays Towards An Aesthetic Philosophy (New York: Horizon Press, 1960) pp. 95-96.

13. Read, The Forms of Things Unknown, p. 198.

14. Read, The Forms of Things Unknown, p. 61.

15. Read, The Forms of Things Unknown, p. 63.

16. Read, The Philosophy of Anarchism, The Anarchist Reader, ed. by George Woodcock, (Glasgow: Fontana, 1986) p. 74.

17. Read, The Contrary Experience, cit. Woodcock, pp. 50-51.

18. Read, The Philosophy of Anarchism, cit. Woodcock, p. 235.

I was struck by this quote: "“It is as simple as that: we have lost touch with things, lost the physical experience that comes from a direct contact with the organic processes of nature… We know it – instinctively we know it and walk like blind animals into a darker age than history has ever known”

What struck me about it was not just how true this statement was and is, but how vastly more true it is now — especially considering it was written decades before the digital age.

Thank you Paul, this is an inspiring essay. 'To live a life despite it all, to find a way beyond the wall of fear, beauty's always here sometimes unseen, between the black and white the light between. Mother Nature shows us how to live and move within the Now. In diverse ways we play our part , enrounded in that boundless heart of Love'